It all started with a phone call. And the telephone, extracted from an n old and outdated spreadsheet, which connected your name to another organization, another slum. That’s how I meet Ezequiel, a potential young leader of the Mathare slum, a few kilometers away from Korogocho.

We sat at a café somewhere in Nairobi to chat before hopping into a Matatu heading to the community. We were analyzing each other. On his side, why in God’s name, a muzungu like me would come closer to a slum? Probable answer: bored with my plentiful life in Europe, I decided to help the poor. On my side, I just wanted to make sure that he was someone with access to the community and able to freely represent – or access – Mathare.

After a few minutes chatting, we adjusted to reality. He understood that my objective was learning, researching, and my intention was to contribute with ideas and contacts from other organizations, at least for a while. On my side, I felt safe that, despite not being currently involved with any organization, the self-defined job as a free-lancer sounded interesting. We talked, I paid for the coffee and we left.

On the way we talked about some ongoing projects, such as the apparently gruesome RYP (Rehabilitation Youth Program) a youth center called Luwaku and a garbage collection cooperative, also carried out by youth of a community called One Love. So many projects related to youth. My question was answered: he was born and lived for over 20 years in Mathare. He knows everyone.

We walked along the asphalted and commercially busy side in the outskirts of the slum. On the way, several signs referring to the international cooperation projects between the Germans and the Kenyan government. In one of the parts of slum (Mathare 4A), a German initiative tried to renovate some houses. It turned zinc shacks into cement houses. Until today it is clear to see the impact of such intervention, but the project was interrupted due to the tribal violence after the 2005 elections.

The region has two well-defined areas (and many others that are undecipherable): on one side, asphalt, 3 to 6 story buildings, public utilities (deficient, however present) and an atmosphere of “normalcy”; some more steps through the landfill, once again a bridge and we get to a second area, apparently with no planning, no infrastructure, e no presence of the public power. But a lot of people living there.

The houses are distributed along one creek and end where a second creek starts. During the rainy season (according to the residents, during practically any rain) the two creeks merge, flooding the narrow land strip that has more than 200 houses. On one side, called Ndoya, a school, blockhouse style, was built and it is one of the most stable constructions in the area, avoiding the constant flooding of the creek. I got used to the smell suffocating odors of open sewerage, but I confess I was knocked out by the smell coming out from the narrow pathway at the edge of the creek.

Surrounding the school the houses are not very well designed and are constantly flooded. The dirt ground, totally flooded and covered in insects is the place for plays and nice smiles of hundreds of slum children. A symphony of “how are you?” comes from the cheerful voices of the little ones, but in my mind the answer is not as positive: how am I? I am trying to find out some feeling that would justify so much neglect and abandonment, so close to the “rest of the civilization”.

The surrounding buildings consider this part of the slum– including its dwellers – a major landfill. Every day they toss from their windows the garbage from their houses, with no regard to the final destination of that waste. But we, here below, know exactly the impact of such lack of respect: piles and more piles of accumulated trash being collected daily by some of the young members of an organization called One Love. However, the amount of trash and the way it is disposed of hinders any nearly acceptable result.

We crossed to the other side of the community, and we arrived to the second creek. A weird invitation: I was invited to see the collective latrines of the slum. I squeeze sideways through a wooden wicket and barbed wire and I reach the creek’s edge. Here, two small houses made of twisted metal and wood serve as a refuge to satisfy the most basic physiological needs of the residents. And obviously, from there the waste goes to the same creek. The background landscape is filled with trash, plastic bags and buildings that surround this part of the slum.

Watching the brown-bluish water that practically does not move, an unpleasant sight. At first we thought it was a doll, a toy that children play with and learn how to care for another being, even if just playing. But it wasn’t. With only one arm and a part of the body outside the area a newly born (or better, an aborted baby) laid there, on a pile of trash that formed an island in that insensitive landscape. I was reluctant to take a picture, but I registered the image. From far away, with no expression and a pain hurting somewhere in my being.

Talking with the residents we understood that this is something that repeats itself very often, not only here. Abortions are carried out through illegal and dangerous procedures, and the aborted fetus is discarded. Just like that. On the other side of the fence a local church building. According to Ezequiel, the marriage of his sister will be celebrated there the next day. And that’s how I took the baby’s image away from my head and replaced it with a romanticized scene of the union between two strangers. Just like that.

I got into a common matatu inside Nairobi, but destiny waited for us a few kilometers from the Kenyan capital. Our transportation dropped us off on an asphalted street, but from there on the path was a dirt alley. An active market took over the scenario, but we were walking on an extremely uneven land, full of cracks and holes, where hundreds of people and some motorcycles circulated. The alley, approximately 500 meters long, is the last existing connection between the presence of the public power and the Korogocho slum.

The end of the alley opens up to an open field covered in trash. A creek separates the open field from the beginning of the residential area, and in an exposed sewerage pipe children play of hanging above the water. We crossed a less than 1 meter-wide bridge and arrived to the main street where the slum begins. We walked on, surrounded by alert eyes and a greeting from a Muzungu that passed by. A left turn, going by several clotheslines, and we at last arrived to the office of the organization I was going to meet with: SUFTA (Societies United for Transformation in Africa).

I was greeted by John, one of the organization founders. According to him, SUFTA was founded by some young people who were born and raised in the community. I asked him to explain how the organization worked and about the ongoing. I admit: I was dumbfolded by the explanation. He talked about strategic planning, social business, empowerment of young people and women, community social development, holistic approach and other terms that so much used today by NGOs and international agencies. I decided to ask a sensitive question and I was quite impressed by the answer.

-John, where does all this knowledge come from?

He answered me with a shy smile. The organization founders are university students who graduated in administration, economics, and community development. It was interesting to check some data that state that a large number of young Kenyans currently attend the universities in the country. And they specifically decided to use the acquired knowledge to return to their community of origin and make a difference. This was much better than the answer I was expecting, regarding some type of a standardized training provided by some organization.

We discussed a new project of legalizing marriages as a way to reduce domestic violence and make men and women more sensitive about the commitment of starting a family. And, at the same time, IT projects, prevention of HIV/AIDS and malaria, development of small business and psychological support are part of a weekly agenda in the community. An international volunteer of AIESEC was also there, teaching English for the local children.

It is estimated that 120,000 residents live in the Korogocho community, and 70% of the population are 30 years old or less. It is considered the fourth largest community in Nairobi, behind Kibera, Mathare (neighbor community) and Mukuru Kwa Njenga. It is an illegal settlement founded in the 80s, by a majority of immigrants coming from rural areas and even Tanzania. The land is divided and more than half of it belongs to the State and the rest belongs to a private owner. There is no presence whatsoever of the public power in the region, and water and electricity distribution is illegal. Most of the water in the region comes to some water tanks and it is redistributed by middlemen, thus raising the price considerably (according to John, the water quality is very poor).

The presence of the government can barely be noticed when walking along the community streets. On the contrary, it is quite easy to realize where the government presence ends, a little before the access bridge to the slum. On one side, running water, public lighting and how can we say it, aligned streets. On the other side, abandonment in the midst of dirt narrow alleys and improvised houses made of metal sheets and mud.

SUFTA supports two local businesses as a way of pursuing its financial sustainability: a candle factory and a tomato plantation. The profit is used to maintain the office overhead and the activities in the community. Although they still depend on a monthly donation given by a British citizen, who “adopted” the project, the organization founders and directors are looking for ways of being financially independent to develop their activities.

I cannot deny that I arrived in Nairobi with my fists ready, in a defense position. I had heard many stories of thefts and scams and the nickname “NaiRobbery” repeated in dozens of forums, guides, books and it was not encouraging at all. When leaving the airport, in the early hours of the morning, it took me over an hour to get into a taxi, since I had to make sure that the price was fair and I was not putting myself in any kind of risk. I approached several muzungos, but none of them were heading to the same direction.

In the taxi, the only traveling option at that time, I talked to the driver and led the conversation to two ways: first, I praised the Kenyan population for being nice and friendly (a schizophrenic attempt to convince him not to rob me); and second, I shared several unfounded stories about myself in order to guarantee that I was not just some stupid guy: I stated that this was my fifth time visiting the country, I told horror stories about life in São Paulo and how used I was to violence; I boasted about fighting championships and my knowledge of self-defense. At the end, I guess the driver thought that I was going to rob him.

On the spot marked with an “x” in my guide, the hotel where I planned to stay no longer existed. Nevertheless, from 2007 until today (the date my guide was published), many other “hotels” opened in that region. The loud music and the different models that strode along the street told me exactly what part of the city I was staying in. After checking more than 5 options and realizing that they were all booked, I finally found a suitable room for those few hours of sleep.

When I went out the next day I realized where I was: basically in the middle of a Nairobi’s “25 de Março” (mixed with Augusta Street). The neighbors gave me a nice reception when I left the hotel n search for an ATM to pay for the hotel. With a city map in hand, in a few hours I crossed Nairobi. I felt like home. In fact, I felt like in São Paulo.

On one hand, people walking in a hurry, many wearing suits and ties, going from home to work to lunch to work and home. The city is also divided in regions: the street of the electronics (Indians and Chinese), the street of textiles (most coming from Tanzania), two large parks with trees, some museums, giant supermarket chains and coffee places and hotels for all tastes. But, where are the slums and poverty? After all, one of the reasons for my trip to Kenya was to explore Kibera (considered one of the largest slums in Africa) and other regions famous for their extreme concentration of poverty.

The subject was not postponed. I sat at a coffee house with two Kenyan friends I met in a UN-Habitat course in partnership with my previous job at the Weitz Center, in Israel. After talking about the location of my hotel and ask about the whereabouts of the slums in Nairobi, we made a decision: I would move in to Stanley’s house and I was going to help him and Debrah to start a consulting business for the development of slums.

The agreement was perfect. While I continued with my research and visited different projects, we would be, at the same time, creating opportunities to continue our discussion through the new consulting business. We quickly assessed the contacts and organizations we already had and started developing a visit schedule for my stay in Kenya.

I retrieved my backpack from the hotel downtown and we hopped in a Matatu* heading to a kind of Nairobi suburb named Uthiru, where Stanley lived. So, where are Nairobi’s slums? In general, they are located in the periphery of the city (not that far). When I said I felt like home, in São Paulo, I was also referring to this dualism. For the “city” inhabitants it is quite easy to spend their entire life without even knowing about the existence of the slums and the life conditions there.

*Matatu is the name of the transportation minivans in Kenya. In the past, they were covered in graffiti, decorated, and competed for the most powerful sound system. I read the report in the wonderful book Pé na África, by Fabio Zanini and I was disappointed because a new series of laws restricted the cultural competition among those vehicles. What was left: worn signs of old graffiti, sound systems working in secret, and the same feeling that each trip puts your life in a Russian roulette. The origin of the word Matatu comes from Swahili and it means something like “4 moneys”, because this used to be the price of the trip. Today, depending on the time and on the weather, you pay 20 to 300 Shillings for the same trip.

This text was kindly translated by Michelle Fidelhoc. Thanks!

We were waiting for the bus like everyone else. Me and a Spanish friend had come down from our first bus, a ride of more than 10 hours, and were then waiting, sitting in an tree trunk, in the midst of a light rain. All of the gazes were focused onour strange presence in that village, making a route that is not so common for farengis to do. Anyway, we had the rest of the way by land ahead of us and we needed a "ride".

We tried to enter the first bus that passed, but were denied permission. Not that there weren’t vacant seats left, but the driver made it clear on some sort of body language that he couldn’t take us before the intermediary defined our differential price. After a series of evaluations, a young man warned us that, if we wanted to catch that bus, we should reserve our seats first, paying four times more than the rest of the passengers.

Suddenly, a light came up: a rich-looking Ethiopian citizen who spoke excellent English was doing the same route as us. He offered to help as our intermediary, but we soon started to realize that the light was not as bright as we had thought. He was actually negotiating the seats of those who were already inside the bus, offering more money and forcing them to leave the bus. We made it clear to him that we disagreed with what he was doing, and we didn’t mind waiting for the next bus and traveling "normally".

Everyone left the bus and a reorganization of seats began. First, our "friend" took the front seat, which is considered to be the best. Then, the boys pushed us into the bus. Right after that, all of the people that were there before us had to squeeze themselves in the remaining seats. As we sat, the prices were put on the table: 20 Birr for everyone, 40 Birr for our friend and his special seat, and Birr 60 for two farengis that can not argue directly with the driver.

Seated, I complained about having a seat that I did not deserve. I complained also for paying three times the price of the trip. And discussed with our "friend" about all that reorganization of seats being simply wrong. Apparently, after some laughs, it became clear that morality and ethics were not a concern for that gentleman, who had just returned from a training for international agencies in Germany. For me, they were. We threatened to get off the bus, but were warned that the procedure would repeat itself in any other mean of transportation that we tried to take.

Meanwhile, among the crowd that watched us, one face was static. His clothes were torn. That is no new in a place where so many children are covered with only a few rags. The adults also seemed to be wearing the same piece of clothing that they were in weeks. The brownish color of the dirt and the wear prevailed over all the other colors, and the smell permeated the atmosphere of the mini-van.

I noticed him looking at me from the moment I got off the first bus. I, of course, could understand that I was new to him. I was impressed with the amount of time he spent watching me. Actually, in Gashena, a village 62 kilometers from Lalibela by land, there is little opportunity for activities, be it economic or social. His black skin was very dark and smooth, but it was covered with dust. His dry lips, almost motionless, outlined from time to time a half-smile.

I did not smile. I was furious with the reorganization of the seats and with hearing the excuse I hate the most: "This is Africa". My gaze was fixed on a boy outside the mini-van. Our eyes didn’t leave each other for a second, and I wondered what he was thinking. Wrapped in a cloth that was once purple, there he was, static, maybe with a head full of thoughts, maybe not.

I don’t know what happened. My chest tightened. My eyes moistened. I was embarrassed. There I was, after more than a year of traveling, shedding tears for some kid in a village somewhere in the middle of Ethiopia. I didn’t hide my tears, but they were unnoticed. The salty water that ran down my cheek was a response for what I’d seen in the last days. And I considered myself so strong and prepared to observe and reflect on Poverty.

There was something in the complexity of that whole scene that made me lose my composure for a moment. I did not cry of pity or sorrow. I did not cry of hatred or anger. I cried, for I did not understand. I cry because I still do not understand how it is possible that two very different worlds live together in such harmony. I cried, but I no longer cry.

This text was kindly translated by Tania F. Cannon. Thanks!Latin America (with a few exceptions), Asia and Africa are very cheap places to travel. Many people chose those destinations because they know they can spend much more time touring, living in different cultures without spending too much. This usually happens because of the disparity in exchange rates, differences in the cost of living or something like that.

However, I would like to highlight a problem, through an example coming from Ethiopia. The amount of beggars and poor people amazed me. Everywhere, people in different stages of health, physical conditions and ages walk along the streets begging for money. The number of people who depend on those donations usually triples in the touristic areas.

Here are some figures, collected from informal talks, to help understand a small problem: the average wage of a hotel maid, receptionist, or security officer in Lalibela, north of Addis Ababa, ranges between 350 to 400 Birr a month (something around U$20.00/month). Those services usually take more than 10 hours a day, in questionable conditions, with no job security and many times, based on a verbal agreement (no labor laws or anything like that). A tourist pays, in average, for a simple and clean single hotel room, approximately 60 to 120 Birr (3 to 7 dollars) for a night.

Let’s suppose that someone feels sorry for a beggar on the street and gives him/her 10 Birr, equivalent to approximately U$0.50. And half an hour later, someone else shares the same feeling and gives them the same amount. And lastly, let’s suppose that all of it took place in a one-hour span, in the morning, when tourists leave their hotels to explore the touristic attractions of the city.

Supposedly, this situation repeats itself every day of the month. If you are also calculating, we are talking about 20 Birrs for a one-hour work , times 30 days a month: a total of 600 Birrs (U$35.00), almost 50% more of the hotel wage. Instead of spending the entire day cleaning bathrooms, and organizing someone else’s mess, with no sign of guarantees or labor laws, begging becomes an excellent option. Much more profitable and much less tiring.

Then, what can be done? I see a solution from two different angles to be resolved simultaneously. I believe it is not enough to tell tourists not to give money to the beggars; it is also necessary to regulate and qualify the work of those people. Those two actions need to be coordinated and job opportunities need to outdo begging.

Maybe the cost of a night at the hotel will go up. Even if it doubles, it is still a good deal for a tourist, and the funds coming from tourism may finally contribute to the development of regions such as Lalibela in Ethiopia. Tourists will have to agree to spend a little bit more for their tips, paying the price to help the development of those communities. And that, of course, only if the money is well used.

The image most people have is that Ethiopia is widely distributed in times of crisis: starvation, drought, poverty and diseases. Skinny adults and children observe the camera lens with a lost and helpless look. Lying in a desert landscape or in the middle of the street, they are apparently desperate for food or help. Well, Ethiopia doesn´t look good in the picture.

Begging is established and socially accepted here. It is more or less expected that a portion of your wealth ends up directly into the hands of beggars from the streets. If you oppose to contribute, this decision is also respected by those who beg. It´s difficult to find a beggar who will talk a lot and will follow the pedestrian for miles. He asks, you answer. And so it is.

It is virtually impossible to walk around the city without having to turn away at some point, avoiding an image that is hard to handle. At the same time, it is impossible to spend time on the street without a spontaneously smiling. Somehow, the (very genuine) friendliness and warmth of the Ethiopian made me feel very welcome. I've never seen people so helpful, friendly and open.

The country clearly lacks basic infrastructure and maintenance. The streets and sidewalks are generally wide and well designed, but the asphalt is flawed, full of holes and leaks. Often, street and sidewalk are mixed in a pile of stones stacked up covering or exposing small lakes that form with the rainwater. Sometimes we observe the sewer exposed on openings in the ground with more than 2 meters deep.

To cross the wide streets, crosswalks are widely respected. Despite the shortage of traffic lights in operation, dozens of police officers organize traffic and drivers are always aware and stop to the safe crossing of pedestrians. Traffic express a little of the country's social disparities. Among walkers wrapped in blankets, mini-vans for public transportation and cars in questionable condition, one class stands out: the middle / upper class of the international aid agencies.

Pickup trucks and 4x4 vehicles stamping the most diverse combinations of initials and logos march through the city. These vehicles stand to the dirty gray landscape of the rest of Addis Ababa, carrying mostly a clean white color. There are some places in the city known for being attended almost exclusively by that class (whether they are foreign or local consultants hired by these agencies).

In the region of Bole, full of embassies and representations of international organizations, we can find a wide variety of products directly imported from the U.S. or Europe, or Friendship Market or Bambi's Supermarket. In addition to the markets, some cafes offer a more, let´s say, Westernized environment. Of course, the prices, though still infinitely cheaper than in the West, reflect certain social disparity. The famous Kaldi's Coffee is the Ethiopic version of Starbucks (or the reverse, as many here say), and as a friend of mine told me, offer besides coffee, a meeting point for farengis (tourists / white people / foreigners) to get in touch with the widespread prostitution in the country.

We hear lots of complaints of lack of job opportunities in the country. And the lack of professional qualification offers the best options from begging than in stressful underemployed. Still, there is a wide variety of "street jobs" such as shoe shiners and shoe cleaners (yes, with soap and water), phone card and books sellers, taxi assistants and, of course, a few cheaters by the areas filled with tourists.

The best job opportunities are with agencies and international organizations. Jobs displayed on bulletin boards along the streets and with companies of job relocation. At the same time, many complaints also come from these organizations accused of investing more money in their own team and well-being than on the specific needs of the country. The great complex of the UN exposes some of that reality.

The country's currency is the birr, which in English sounds like "beer". Perhaps cordiality comes from there, after all, every debt is resolved by paying a few "beers". The bills appear to have been printed once in the past and never again. They dissolve in our hands and smell really bad, giving the impression that they are circulating for a long time. In various bills that passed through my hands, one was marking 1995. The problem is that, knowing that the calendar used in Ethiopia is eight years late *, these bills may have more than 20 years.

Despite the urban esthetics of the country being unfavorable to the lens (but favorable, of course, to the sensationalism), the feeling of traveling the main streets and small alleys is that you are at home. Well, actually I felt much safer here, walking by night and in total darkness than at home, but each one with their own problems. Ethiopia, then, does not look good in the picture. But outside the television screen, or magazines and newspapers pages, the country brings a charm mainly characterized by the human coexistence.

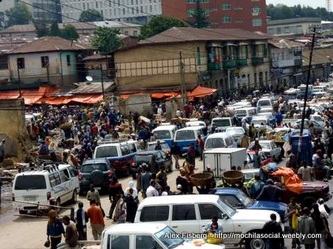

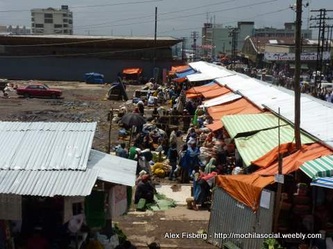

The market carries the Italianized name of a time of foreign control over the country. But, with no doubt, walking along the little alleys of the place, it is Africa: from stigma to reality. Chaotic, disorganized and no planning, the market offers all kinds of merchandises. And all types of landscape as well.

In less than a twenty minute walk I was already at the center of Mercato. I didn’t go alone. I was accompanied by a local boy who, according to his story, had worked for three months in the local census. However, within a few minutes walking, several people approached him smiling and shouting “Ganja” (which I know from my previous trip to India that it means marijuana). I don’t care. I am more interested in the fact that he has access to and respect in the region, enough to take me away from the touristic beaten path and show me, more in depth, the hidden secrets of this anthropological nook.

Our path shows streets with no asphalt, with no clear definition of beginning or end and is muddy due to the rainy season. An intense movement of people, animals and merchandise. Work horses, goats, beggars, mutilated and sick people circulate with no distinction. Sometimes, lying on the ground, a corpse, either human or animal. During my conversation with my improvised guide I can see over his shoulder a gray and painful landscape. No one seems to note my presence. But my thoughts seem to be plugged to a 220v current.

In terms of businesses, the stores are more or less grouped by activity. Coffee growers on one side, iron handling on the other (exported mainly to Chinese companies for road construction). Vegetables are cut and distributed on the ground of a narrow alley; moving along is quite impossible; clothes and fabrics are manufactured at the end of the long corridor.

Wearing sandals I can feel between my toes the insalubrity of the place. And when I watch the children and the handicapped lying on the same floor that causes me so much discomfort, I feel my feet a bit heavier when I move. I ignore the fact that I saw a dead rat. I am distracted by a beggar whose skin is taken by large blisters and wounds. He exposes his body in the middle of the street and, even though, manages to have looks diverted from him. Not mine. I am no longer looking at him, but his image is etched in my brain.

No time for reflections. Then we entered a symphony of youngsters and children, almost synchronized, hammering long pieces of iron. The raw material must be exported to China. And the profits are also going to the Chinese. Huge pieces of a whitish seasoning are hastily cut and offered to the pedestrians who crowd the few centimeters between the tents.

Most of the clothes are stained in brown. Although some of the clothes and scarves originally had bright colors, wear and tear is stamped on them as a brand label: Ethiopia. There is an area for seasonings. There is an area for craftwork. And there is the “clean” part, with souvenirs and mementos from Ethiopia, inhabited by some few differentiated faces in the crowd: the farengis. Caucasians, foreigners.

Lurking around there is always a crowd of beggars. In a way, they respect the decision of passers-by to share or not their small wealth. On one corner, some officers with their wrinkled uniforms watch the crowd. I witness a theft followed by persecution by the police officer. All fake, accoridng to my young guide. Later on, both will split the profits and many times they also split the rewards for the apprehension and return of some valuable.

From the second floor of a small business I watch and, for the first time, I take pictures. There is no way to capture the energy of the place, nor its several smells. The camera’s lenses cannot see what I am watching. I go downstairs avoiding someone in a wheelchair, whose arms move a pair of pedals. He is being pushed by a young boy covered by a filthy cloth, and together they beg for help. Not to me. My presence here is barely noticed, and I can’t understand why.

The Mercato moves several industries in the city. On one hand, Chinese use the iron produced in the region to build roads, while the Indians explore the manufacturing market. All get together at the market to buy several types of goods. And many see the Mercato as a business opportunity, a place for alms or for a theft. There is room for everybody and, at the same time, everybody tries not to touch others.

A residential area surrounds the market and shelters a major part of the families that work at the Mercato. Alleys of rocks and earth, much less populated. Lying on the ground a few more bodies. It is impossible to understand the vital status of each one of them. While some seem to have chosen the place to get established, with an outstretched small plastic piece in front of them and looking for charity, others seem to have died for lack of option. The residential area is not made for visitors; therefore, I do not spend much time there.

On my way back I opt for a long walk. Several images come to my mind and I need some time to review them. The place is considered one of the largest outdoor markets in the African continent, but I am sure that the place is much more than that. I leave without buying anything, I was told not to carry anything with me. But I take as my luggage a lot of images and impressions of what goes on there.

This text was kindly translated by Tania Cannon. Thanks!I made a point in arriving to Addis Ababa, the Capital of Ethiopia, from Cairo, traveling with an Ethiopian national carrier, the Ethiopian Airlines. The reason: simply in order to get into the mood. But, I was taken by surprise by multiculturalism, expressed by the different faces and nationalities in my flight. Europeans and Asians (mainly Chinese and Philippines) mixed with an array of Africans, and, in fact, maybe a minority of Ethiopian (a phenomena muffled by the interactions in English, French or sign language spoken by the flight attendants).

Before going through immigration, I needed to have my entry visa for the country. Twenty dollars and tem minutes wasted later I had my new visa stamped in my passport. Then, in a few minutes, I breezed through immigration and left the airport. I was met by an Ethiopian friend, Afework, whom I met during the course about poor neighborhoods/slum improvement through my former job in Israel. It was both a pleasure and a relief to see him. With him, I stayed away from the private cabs that surround the airport and we walked for 10 minutes until we reached the shared taxis outside (“lotação” style)

We changed vans in an area called Arat Kilo and we headed to the region of Piazza, where backpackers in general end up staying. We had some coffee at a local restaurant and I realized it was similar to and had the same quality of the Brazilian coffee, mainly in the way of drinking it, the cafezinho. Later on I found out that that around my hostel – and around all Addis – a large numbers of coffee places characterizes the city. Thousands of Ethiopians’ sit down, at any time of the day, to drink a cup of coffee, a Machiatto or a capuccino.

Ethiopians are famous for their hospitality and their respect for etiquette, but I knew that my friend needed to go back to his routine, so I kindly asked him to trust me, I would be fine. I went back to my hotel, unpacked and went to explore the region. As soon as I left, I was approached by a well-dressed young man, with an impeccable English accent and so nice that any Egyptian would be envy. Even with my gloves on and my fists ready, I decided to chat with him and I was taken aback.

Just a note before I go on: from the beginning I knew this was a kind of a scam, a trickery, or something along those lines. However, I still trusted my abilities of making decisions, my power of persuasion and my good pep talk to get me out of trouble. And at the same time, my curiosity in understanding this type of deals always keeps me going. Cautiously.

We talked while walking together to the market – I had mentioned to Yonatan, my new friend, my need to shower, and consequently, the need for a shampoo. As we walked along he told me his story: 25 years old, studied literature at the University of Addis Ababa, currently on vacation, lives close to the region I am staying in, and would like to practice his English. If I said I needed to go left, he would tell me he was also heading that way so, in such a way, I decided to use him.

I was planning to visit a region called Mercato, 20 minutes walking distance from my hostel. It is one of the largest – and most chaotic – markets in Africa. I had read about the region and I thought it could be a good place to start observing the daily life around here. Thus, I told Yonatan that I was going to take a shower, leave all my belongings at the hotel and we would go together to the Mercato. I made a point in making it quite clear, before and during our walk, that I was not carrying anything on me, and this would bring me some freedom.

I’d rather write a separate text about the specific description of the Mercato. In fact, it was the entry point for a quite impacting Ethiopia and, insensibly on my part, I expected something like that. We walked; the ground was not even, not planned and humid due to the rainy season. We entered through the route that all the tourists usually visit (normally led by tourist guides) and we walked through small alleys and residential areas surrounding the market.

After more than two hours of going in and out of that region we headed back. We talked about soccer, housing public policies and life in Ethiopia and in Brazil. He was taking me through a way a little bit longer than that we came from, and I made it clear, but in a jokingly way, that I knew exactly where I was and how to go back. As we approached the hostel, he asked me what my plans were next. He asked me if I was willing to “have some fun”, chew Qat and exchange some deep ideas with him and his friends. I told him that, unfortunately, I was here to work, I had to go back and write, and later on I was meeting my friends here.

I wrote down his phone number, for a future gathering. The whole time I made jokes such as: “I don’t need your phone number, Í am sure you are going to be here tomorrow looking for people like me”. He laughed, and I guess he understood that I was not really in the mood to fall for a scam. I went back and got some rest. I needed a break. I was very tired from the trip and had a heavy heart from the things I observed in the Mercato.

After I woke up I went for a cup of coffee nearby and, on my way, I was approached by two youngsters with the same story. I led them on. And when I returned I was approached by another one. I also led him on. That evening, when I left to have dinner, by myself, I decided that there was limit for the scams, and that without day light nothing would be as safe, so I decided to have dinner at a restaurant across the street from my hotel. For the first time I ate an Ethiopian meal: Fir Fir meat, with injera, the traditional bread of the region. Surprisingly the taste did not bother me, but of course I did not eat even half of my plate (with my hands. of course).

I am going to write about what I researched and learned about the scam of the “Ethiopian university youngsters” whom I was talking to: After they introduce themselves and gain your trust, sometime after cups of coffee or mugs of beer in local restaurants, they invite the tourist for an activity and then offer a free service. Something like a local music presentation (even if in a CD) or the consumption of Qat and some chat (Yonatan told me that those chats are nicknamed “Facebook”).

And then, at the end of the group experience– normally far away from the hotel, in some place where they have better control – they charge, under threats, for the rendered “service” (I don’t know and don’t want to know how severe those threats are). Something around 2000 Birr (more than U$100.00), according to what I heard from tourist who have been here for a while. The thing is that in a coffee place or a bar they cannot scam tourists. They can only act when the “product” belongs to them, and cannot have a price tag on it. Note: the stories they tell are very well concocted and even facing some tricky questions, most of them did very well (of course with some incoherencies and discrepancies, but they are not perceived by the, unaware tourist).

And I thought I could suggest to Yonatan to become a professional in his service as a “local guide”, with good reviews in all the online traveler sites. I also talked for a long time with another youngster named Tony. We got to the conclusion that the scam was already well known, and I suggested to approach tourists in a more sincere and straight manner, in exchange for some Birrs. Something like: “I am a young Ethiopian, local resident and I know the region. I offer to be your guide/safety contact in the region for X Birrs”. He, of course, agreed with me, but I seriously doubt he will change his ways.

As days went by I became more and more interested in that subject. I talked to dozens (!) of youngsters on the streets of Piazza, and to many backpackers. Some of them had been victims of scams (an Austrian girl and her boyfriend lost 500 Birr in one of those “chats”). I had a long conversation with two youngsters and I gave them a stern suggestion to change their strategy and turn them into local guides. We talked for at least 1 hour; we discussed prejudice, Africa, Brazil and the impact of tourism in the region.

All along both nodded, praised me for my different approach and thanked me for the opportunity to exchange ideas. Meanwhile, on the streets, dozens of beggars went by, apparently in worse health and social stability shape. We got to the conclusion that not all the tourists are the same and not all the youngsters in the region are trying to scam someone. When we said good bye they had a last question: “Alex, would you pay us for a blessing for your safe trip?”

I smiled at them, shook their hand, Ethiopian style, and left.

This text was voluntarily translated by Ilan C. Kochen - Thanks!

From the minute I stepped into the city until the glorious moment that I got on the plane heading towards Ethiopia, I felt that myself experiencing some kind of scam. After nine hours by bus and cautious researches in my travel guide and with my traveling companions about how much should cost a taxi ride from the station to downtown, I got off the bus to hear an amount six times greater.

Regarding the attempts to exploit tourists, I must confess that I´m used to this from my experience in India. I think what affected me the most in Egypt was the basement of these lies. It is not enough to charge abusive prices. The strategy is to try to convince tourists that everything will go wrong and the best option is to rely on the new “friend”. “The bus? It´s no longer coming this way”; “Your hotel is closed”; “It´s too far, the bus is not coming and you better take my cab”.

I checked one information on the Internet, and then checked again in the guide, talk to backpackers and as I went out to the streets, everybody was trying to convince me of the apocalypse. Usually the hostel staff is very helpful and gives tips on how to avoid cheating. But not here. My worst enemy was the reception, which held me for hours trying to convince me to hire several services before checking the streets of the city. But I´m stubborn.

I left in the morning to withdraw some money and thanks to the inefficiency of my bank, wasn´t able to do it. The door was open for an ordinary passerby to approach and offer me the purest of friendships. After him, four others offered me exactly the same friendship, even with the same personal information and proposals. I came to believe that all people live in Giza (that´s where the pyramids are) and love to have dinner in the company of tourists like me. I believe I would have been one of the main dishes.

I ended up going to the pyramids by bus, following the unpretentious advice of a water seller, who could not take advantage of my question (because I had already bought water from him). Forty minutes later the driver shows me one of the pyramids that could be seen from the street. My Arabic is as fluent as his sign language, but it was clear that there was only one way to follow. Twenty minutes later, I´m facing the entrance complex of the pyramids. And was particularly perplexed.

I had heard that the pyramids were located right in the middle of the city, but had no idea how this influenced the climate, the topography and impacted the landscape. From one minute to another I found myself in the middle of the desert, with a bottle of water in my hand, shirt tied around my head and sunglasses. Among the crowd of camels, horses and all kinds of offers, I decided to explore the monuments on foot, saving my money and my patience. After walking for 20 minutes under the blistering sun I made an interesting geometrical discovery: pyramids do not produce shadows at any time of the day.

The pyramids are really impressive, but I confess that what interested me the most was the contrast between city and desert. Some steps climbed up in the second largest pyramid exposed this contrast: in the foreground a secular pyramid, an altar of celebration of the continuity of life, and behind, the urban expression of how this life continued.

I do not know exactly the ideological line and the real motivations that led them to build such monuments, but I feel that the ongoing discomfort caused to the tourists would not please them. There are endless offers of products and services in this area. I watched Japanese, Italians and Russians fighting with vendors and cops to get rid of unwanted services. The white cops provide a significant disservice: they offer the so-called best view of the pyramid, with photographs included, in exchange for some Egyptian "Bounds" (Arabic pronunciation, replacing the "p" with "b").

I then decided to return. A bus took me to the train, which led me to Tahrir Square. From there, I tried to enter the Egyptian museum, but due to Ramadan, the opening hour was changed and I was excluded from the experience. No problem, my interest in this single day was more focused in the square than on tourism itself. After all, Egypt is experiencing an interesting transition moment and I was there in the middle of the mess.

The presence of the police and the army is just for precaution. Another instance of Mubarak's trial is scheduled for the day and the nerves of the country rise. Trucks bring dozens of armed cops dressed in black, while camouflaged soldiers hold machine guns from the top of their tanks. No mess around, and after five o'clock a lull. I was told that people went home to watch the trial broadcasted live on national television.

I also fasted on that day, along with millions of Muslims for Ramadan. Fasting begins around three in the morning and ends with the sunset. I felt the differentiated taste of a Shwarma, but even with hunger the dish did not surprise me. It was interesting to walk and see different public events of breaking fast over the adjacent streets. Within minutes, the whole city turns into a huge restaurant, with everyone breaking their fast at the same time.

After struggling against offers to pay three times more in a taxi, I went to the bus station and waited. And I waited a little longer. After one hour and my bus never showing up, I decided to give up and get a cab. In a few minutes I was at the airport, ready to catch the flight to Ethiopia. I was surprised by the diversity of people on the plane on a flight in the middle of the week, at dawn, from Cairo to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia's capital.

Obs: I decided to decrease my stay in Egypt because of the relevance of this country regarding my proposal. In other words, I was counting the days to get to Addis Ababa.

This text was voluntarily translated by Rafaella Danon Schivartche. Thanks!

- So, this is the Suez Canal?

-Yes... What do you know about the Suez?

-Well, what everyone knows…

- Haven’t you heard about the revolution?

This was how I started talking to Mina, a young Egyptian man of 22. During the next 3 hours we would talk about the recent Egyptian revolution, which began on January 25th, 2011, of the recent demonstrations for justice in Israel, about Brazil, and about life. During the 9 or more of our bus trip between Dahab, in the Sinai, and Cairo, in Egypt, I had both the pleasure and the opportunity to listen to the opinions of a young Egyptian amidst a revolution in his own country.

Before I let Dahab, I talked to the manager of my Inn in the effort of trying to understand what kind of impact the revolution – Arab Spring - had in a region like the Sinai. With a smile on his face, he answered my questions euphorically, as if the issue was a motive of pleasure to him. He could easily be included in the crowd on the streets, even though he had not been there, saying that the end of the Mubarak regime brought opportunities for the country’s reconstruction.

Tourism in the region, according to him, had not altered much since the Egyptian struggle, but the regime’s downfall would ensure more control and development of the Sinai region, which nowadays suffers from the occupation of different groups such as terrorists and hosts a series of illegal activities inside it’s mountains and vast territories, mostly at the north and at the border with the Gaza Strip. He talked and I could feel that not only he included himself in that movement, but he expressed feelings of freedom in his speech and in the head gestures of the driver, also in his twenties.

Outside our bus, I listen carefully to what Mina tells me. He too was there, in the Tahrir Square (Midan Tahrir) when the Egyptian youth decided to put an end to the 30-year-old regime. “No one could foresee, even a day before, what was about to happen”, he says. “Who lead the movement? The common feeling stored somewhere deep in every Egyptian”, he adds.

He looked into my eyes and with pleasure repeated the expression “Game Over”. “The people decided to look in the eyes of those in charge and say: Game Over!”. The bus runs smoothly, the road is excellent and the conversation was being held under a beautiful sunset, privilege of the over 300 kilometers of the west cost of the Sinai desert. In the landscape, on one side the blue ocean water, that no camera can ever capture, and on the other, a desert scenario exactly as I pictured it would be. Mina’s voice won over the Stooges of the Orient movie that was being shown on the bus’ small screen.

And now? How will the post-revolution movement come about, especially if Mubarak is tried, I ask defiantly? “It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter exactly who will come to govern the country. The Egyptian people has shown itself united against an oppressive regime and has publically demonstrated a dissatisfaction that had been kept away from public eye over the years. The time now is to strengthen the Egyptian people”. I confess to have been a bit unsatisfied with this reply, but I can also understand the moment of euphoria and decided not to ruin the glow in his eyes with more profound questions.

As to the calmness noted in the last few days, he tells me that demonstrations have diminished not only because of Ramadan (actually, Mina is catholic), but also because of some of the demands of the people are being met by the military coalition that is guaranteeing the country’s safety. But he warns me: the military Friday is not a day for Tourism in the Tahrir Square, periodic public demonstrations continue and many of them end up in stray bullets.

I arrived in Cairo at night and after a long search for a hotel (being so luck as to find one of the dirtiest and poorly managed of the region) I was impressed with the intense movement of people on the street and followed them to the Tahrir Square. There, I stood observing together with the crowd (minuscule if compared to the number of people that had been at the Square lately) the moving around of the police troupes occupying the center of the Square and the many military trucks that surrounded the place.

I was approached by a young man wearing a T-shirt with broken shackles and the flag of Egypt. He wanted to know my opinion. Soon we were joined by a few young others and talked briefly about all that was happening. He showed me a photo of his brother, who was killed in the demonstrations, and also said he had been shot in the right leg. Nothing happened that time in the Square, but apparently visiting the region became a routine for many young people of the country.

I asked for one last comment from Mina. I want to know how he sees the Israeli demonstrations calling for social justice. With enthusiasm similar to that expressed by his own history, he blesses the demonstrations and welcomes the neighbors’ initiatives. I share my photos of the protests, the tents and banners displayed during the demonstrations and see his eyes light up when reading one of them in Arabic: "This means: move, get out. It was used in the statements of Tahrir Square and we all saw this tribute here through Israeli newspapers. "

From Sinai to Cairo, across the country, young people seem to not only celebrate the revolution that I followed in the papers, but also a new opportunity to express themselves. Throughout all trade in the region, flags and clothing shouting out to love and appreciation to the new freedom in the country. My shirt said: "The power of people is stronger than people in power"

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed