In the last week of September, Dadaab, the already most famous refugee camp in the world won another title: third largest city in Kenya, overcoming the city of Kisumu, next to the border with Uganda. With thousands of Somalis arriving every day, escaping the draught and a violent government self-imposed by the Al Shabaab group, the refugee population in the city exceeds already 430.000 inhabitants.

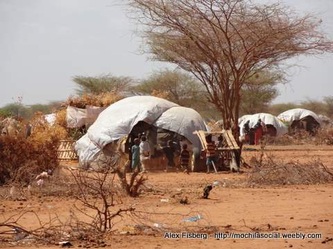

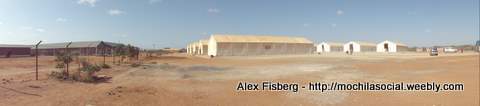

There is no doubt that this is a unique city. It is a mix between temporary and the challenge of getting settled in a region impacted year after year by strong draughts. This dynamics leads the different populations of the region to have, to say the least, interesting relationships. More than 35 international agencies work in the area, and they have their own complex, protected and distant-enough refugee camps. Kenyans, muzungos and even Somali refugees work at the complex, based upon an incentive policy to reabsorb that population (the so-called incentive worker).

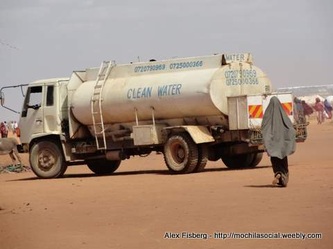

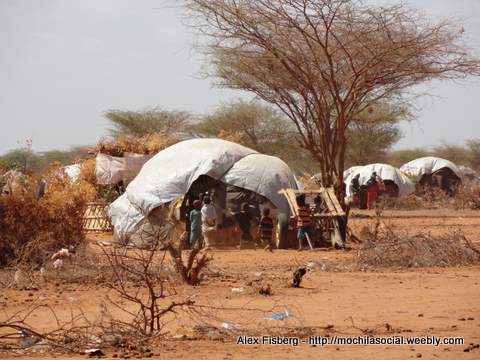

During the 80s, the camp was designed to shelter up to 90 thousand people. Today, it bears 5 times more of the anticipated capacity, and new expansions and new camps are being seasonally planned and built to receive the increasing flow of Somalis. The services offered to the refugees lead, many times, to troubled relations of the local community (host community) with the government and the humanitarian-aid agencies. After all, while those who have refugee status receive all the necessary goods for free, such as water, cooking devices, blankets, and aid to build shelters, the local Kenyan population, who is o affected by the draught, struggles to survive and to receive any available leftovers from the refugee camps.

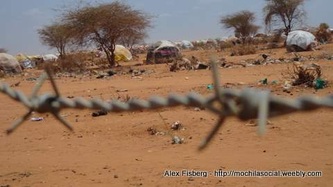

Driving a 4x4 we crossed the sand road opened in the middle of a desert landscape towards extension “A” of the IFO camp, where we would have our first contact with the local struggling Somali population. Our first stop was at a huge WFP warehouse complex, where readymade food was distributed to the refugees by means of other agencies. WFP is in charge of distribution in Dadaab, and has been using different products trying to ensure nutrition for those people. One example is the Plumpy Nut, a type of caloric-powder bomb, widely distributed in different versions in Dadaab camps.

It is impossible to deny the need for emergency care for the refugee flow that arrives daily to the camps, but after more than 20 years, some things could be done differently. The political plot of the region benefits neither the local population nor the refugee community. On one hand the Kenyan government has its eyes quite open to the challenges, but also to the opportunities that a humanitarian crisis in the neighboring country may generate. On the other hand, Somalia, which does not have a well–structured government, is fighting the extremism of a radical group such as Al Shabaab, but receiving only an uncompromising support from the so-called “International Community”.

There is a lot of potential in the region between the far east of Kenya and Somalia. Despite the draughts, it is possible to find natural underground water sources or find them at viable distances allowing for the construction of ducts and pipelines for irrigation. After all, there is an unremitting transportation activity of food supplies, so it would be very plausible to turn the refugee camp into a small-plot camp of productive land. The investment would not be much different from the figures spent today in the region and, in the case of a resolution in Somalia, the refugees could return to their lands with some survival techniques and even some income.

The main problem is the lack of stability in the region and the crisis solution being just an “organized Somalia”. The Somali population has nowhere to resort to in their own territory, since the FRA, the group opposing Al Shabaab, still lacks enough strength to take the power (and according to the representative of a French organization that works on the other side of the border, it is still unknown if they really are the “good guys” of the region).

In one of the schools built at the exit of the IFO camp, the Principal shares some of the challenges he faces there: high rates of girls abandoning school because they have to give priority to the work at home for the survival of the family ; student/teacher ratio exceeding the hundreds, as opposed to the recommendation of the Kenyan Ministry of Education, which is 1-40; one book for every 72 children; and the constant challenge of incorporating newly-arrived orphans, who come to the school for a second chance.

The objective is not to settle those children there. The goal is to prepare them for the national and international tests in universities, mainly the private ones, where there is less red tape. Therefore, says the Principal, some of the students that managed to attend Kenyan or even Princeton Universities become role models for the other children, and many times those youngsters return to the region to somehow contribute and give back to the community.

We did not have any surprises walking along the camp: dozens, if not hundreds of children surrounded us. With startled looks, different from those who were simply interested in what is different, they watched us from a safe distance, avoiding direct contact. The bravest ones came closer, and were received by us with smiles and attempts of physical contact.

In a few minutes, dozens of children were reaching out their hands for a “high-five”. As if it were the first time in their life they participated in some type of playful games, they were divided between those who laughed and those who ran away fearing what would come next. Their upset smiles, many times hidden under a piece of cloth, would open their faces, for the first time, for the experience of playing something different than pushing water gallons or following the steps of an adult. At the end, obviously, children are just children, and deserve nothing more that everything we have to offer.

One of the reasons I went to Dadaab was to try, once again, to understand the parallel of the “temporary-definitive” phenomena. Such phenomena was also observed in most of the slums I visited, where a situation that was supposed to be temporary, a transition phase between a negative situation and the opportunities for a better life, ends up becoming a burden for an entire generation or even more. Of course, in the case of Dadaab there is a clear involvement of two nations and an endless number of external players coming from all parts of the globe. So what is in fact, the difference between a slum in Nairobi inflated by Sudanese immigrants, and a slum in Kampala, with a Congolese majority? They are also suffocated by international aid of the most varied flags and stuck to a “temporary-definitive” logic and vision.

There is no doubt that this is a unique city. It is a mix between temporary and the challenge of getting settled in a region impacted year after year by strong draughts. This dynamics leads the different populations of the region to have, to say the least, interesting relationships. More than 35 international agencies work in the area, and they have their own complex, protected and distant-enough refugee camps. Kenyans, muzungos and even Somali refugees work at the complex, based upon an incentive policy to reabsorb that population (the so-called incentive worker).

During the 80s, the camp was designed to shelter up to 90 thousand people. Today, it bears 5 times more of the anticipated capacity, and new expansions and new camps are being seasonally planned and built to receive the increasing flow of Somalis. The services offered to the refugees lead, many times, to troubled relations of the local community (host community) with the government and the humanitarian-aid agencies. After all, while those who have refugee status receive all the necessary goods for free, such as water, cooking devices, blankets, and aid to build shelters, the local Kenyan population, who is o affected by the draught, struggles to survive and to receive any available leftovers from the refugee camps.

Driving a 4x4 we crossed the sand road opened in the middle of a desert landscape towards extension “A” of the IFO camp, where we would have our first contact with the local struggling Somali population. Our first stop was at a huge WFP warehouse complex, where readymade food was distributed to the refugees by means of other agencies. WFP is in charge of distribution in Dadaab, and has been using different products trying to ensure nutrition for those people. One example is the Plumpy Nut, a type of caloric-powder bomb, widely distributed in different versions in Dadaab camps.

It is impossible to deny the need for emergency care for the refugee flow that arrives daily to the camps, but after more than 20 years, some things could be done differently. The political plot of the region benefits neither the local population nor the refugee community. On one hand the Kenyan government has its eyes quite open to the challenges, but also to the opportunities that a humanitarian crisis in the neighboring country may generate. On the other hand, Somalia, which does not have a well–structured government, is fighting the extremism of a radical group such as Al Shabaab, but receiving only an uncompromising support from the so-called “International Community”.

There is a lot of potential in the region between the far east of Kenya and Somalia. Despite the draughts, it is possible to find natural underground water sources or find them at viable distances allowing for the construction of ducts and pipelines for irrigation. After all, there is an unremitting transportation activity of food supplies, so it would be very plausible to turn the refugee camp into a small-plot camp of productive land. The investment would not be much different from the figures spent today in the region and, in the case of a resolution in Somalia, the refugees could return to their lands with some survival techniques and even some income.

The main problem is the lack of stability in the region and the crisis solution being just an “organized Somalia”. The Somali population has nowhere to resort to in their own territory, since the FRA, the group opposing Al Shabaab, still lacks enough strength to take the power (and according to the representative of a French organization that works on the other side of the border, it is still unknown if they really are the “good guys” of the region).

In one of the schools built at the exit of the IFO camp, the Principal shares some of the challenges he faces there: high rates of girls abandoning school because they have to give priority to the work at home for the survival of the family ; student/teacher ratio exceeding the hundreds, as opposed to the recommendation of the Kenyan Ministry of Education, which is 1-40; one book for every 72 children; and the constant challenge of incorporating newly-arrived orphans, who come to the school for a second chance.

The objective is not to settle those children there. The goal is to prepare them for the national and international tests in universities, mainly the private ones, where there is less red tape. Therefore, says the Principal, some of the students that managed to attend Kenyan or even Princeton Universities become role models for the other children, and many times those youngsters return to the region to somehow contribute and give back to the community.

We did not have any surprises walking along the camp: dozens, if not hundreds of children surrounded us. With startled looks, different from those who were simply interested in what is different, they watched us from a safe distance, avoiding direct contact. The bravest ones came closer, and were received by us with smiles and attempts of physical contact.

In a few minutes, dozens of children were reaching out their hands for a “high-five”. As if it were the first time in their life they participated in some type of playful games, they were divided between those who laughed and those who ran away fearing what would come next. Their upset smiles, many times hidden under a piece of cloth, would open their faces, for the first time, for the experience of playing something different than pushing water gallons or following the steps of an adult. At the end, obviously, children are just children, and deserve nothing more that everything we have to offer.

One of the reasons I went to Dadaab was to try, once again, to understand the parallel of the “temporary-definitive” phenomena. Such phenomena was also observed in most of the slums I visited, where a situation that was supposed to be temporary, a transition phase between a negative situation and the opportunities for a better life, ends up becoming a burden for an entire generation or even more. Of course, in the case of Dadaab there is a clear involvement of two nations and an endless number of external players coming from all parts of the globe. So what is in fact, the difference between a slum in Nairobi inflated by Sudanese immigrants, and a slum in Kampala, with a Congolese majority? They are also suffocated by international aid of the most varied flags and stuck to a “temporary-definitive” logic and vision.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed