I cannot say I was an innovator. Maybe I was just spontaneous, but anyway, the final result of a small experiment ended up being quite interesting. Very simple: inspired by a documentary I watched quite a while, called Born into Brothels, I simply gave my camera to a group of kids of the Namuwongo community. The results are worth an analysis and, why not, some considerations. In my opinion, photography is the recording of a reality. The eye of the photographer decides what deserves to be registered and the elements that will be part of each photo. Banalities are set aside, whereas different motives and choices are behind each click. Instead of analyzing and letting the beauty of such exercise get lost, I am simply going to be the “curator” of this exhibit of children looks. And if one wants to comment, reflect or philosophy, the floor is open. The important here is that this must have been the first time that those children have touched a digital camera. I did not give any explanation as to how the camera works. Even though, a few minutes later, they were already exploring the buttons, discovering how to work the zoom and check the pictures taken. They would pass the camera to each other being careful not to block the lens with their hands and afraid that I would get the camera back. Thus, during that half hour photographic experiment, they took more pictures than I did during a major part of my journey. Just a reminder, our kids have their eyes well open to our plans for their future. If we neglect their needs, or if we fail to build a fairer society, they will be there, in a not-so-distant future, making the same criticisms that we do to the past generations. Maybe it is time to start changing the pictures that our children are taking of this world. Maybe this is the time to stop thinking about photos, videos and internet and start working to make the possible changes. Below is the exhibit of some of these pictures:

The town was painted in three colors: red, yellow and black. On the printed shirts, flags, and on the faces of the young and the children on the streets, the colors of Uganda prepare the country for the greatest moment in the last 30 years: a chance for the national soccer team to advance and dispute the AfCon (African Cup of Nations).

Wearing a t-shirt for Brazil I arrived at the Nelson Mandela stadium at noon. The deafening sound of the vuvuzelas, mixed with whistles and shouts of support for the players– and, sometimes for some politician, such as President Museveni – made the stadium rumble. The beautiful image of the bleachers, the excitement and the union of the country were printed on the faces of the fans, while the lawn was still empty: the game was only scheduled to start in five hours.

On the cement bench, squeezed among other fans, three Brazilians watched the same soccer fever as the soccer country. On the big screen, a message subtly pushed the players to the victory over the team from Kenya: “We have been waiting for this moment for over 30 years”. The talks of most of the fans expressed the certainty of a victory and the classification of the team. The party in the stadium could be compared to the finals of the world cup having the host country as the favorite team.

However, all that energy has a cost. Sitting in front of us was a common citizen. Surrounded by friends, he expresses in gestures and attitudes a major social problem still quite present in the region. From time to time, people move around the bleachers looking for the increasingly scarce empty spaces to watch the game. From times to times, one of those people was a female, and then the problem arose and spread out.

Daylight did not prevent his hands from exploring the breast and buttocks of the girls passing by. Neither did his friends, not even those who escorted those women say a word. If they do, they smile and greet the offender with a handshake and a smile. The women, who could not react due to social pressures, lowered their heads or expressed in their eyes a faint displeasure. Around us, nobody seems to bother about the violations of somebody’s body. Except for the three of us.

A major slap on the head of the guy was not enough. Maybe the booze, the excitement or, unfortunately, maybe ignorance regarding the severity of the offense, emptied the effects of our manifestations. Our friendship ended there. We no longer had anything to do regarding the attitudes of the guy and we no longer expected anything from him. And much less from the others around him, who did not do anything and, as a consequence, reasserted the attitude of inequality and disrespect.

The colors slowly began to lose their brightness and when the game finally began we had already lost a major part of our energy. Obviously, the “show” on the field also contributed to it. A few minutes and dozens of yawns later, it was clear why they waited for thirty years: the players barely knew what to do, and both the ball and the fans suffered.

By chance, I was fasting that day. It was the most important day in the Jewish calendar, and I decided to keep the tradition, even if out of context. I prepared a snack to break the fast, but I was stopped at the entrance to the bleachers because plastic bottles were not allowed inside the stadium. With a broken heart – and the certainty that I was going to feel ill – I left my bottle outside and got in. I saw hundreds of people in the forbidden area carrying bottles similar to mine. I asked them how they managed to go by with the bottle: “Ah, you just have to pay the police officer... 1000 shillings (the equivalent to some cents)”.

At the end of the game, with the expected 0X0 score, two things were quite clear: 1) the reason for the plastic bottle prohibition. They were flying everywhere, hitting the field, the policemen and whoever was in their way; 2) the intensity of an ever present corruption. If every bottle there was brought in as a result of bribing one or more police officers, millions of shillings and thousands of illegal deals were conducted, not quite behind somebody’s back.

This text was kindly translated by Tania F. Cannon. Many thanks!I learned my lesson: planning is important, but having the ears and the heart open makes much more difference in my day-to-day than following itineraries. I arrived in Uganda almost at down, after traveling almost 10 hours in a bus that looked more like a ship: wood ceiling with round lamps, seats torn from an old living room and screwed to the carpeted floor and individual plugs decorated in gold (ok, golden).

I got off in the middle of the road to follow the instructions sent by my Couchsurfing contact. Carrying my house on my back and my office on my belly, I get always a little antsy about walking around displaying my belongings. And, this time, I froze for seconds, without knowing exactly what to do. The situation was the following: I should follow straight to the street ahead of me, turn the first right and after three blocks turn left, pass an antenna and enter through a gate marked by diamond-shaped rocks. Easy, if not for the total darkness (not even a light source in a gigantic radius) and the total loneliness of the moment.

I started walking towards the darkness, but I went back to the road. Then, I resumed walking, feeling as if I just got into a very cold shower. After all, if the instructions were to follow this road, and my colleague knew that I would be arriving at this time, nothing bad could happen. After the first turn, the lights of a car lit the road, but just for a little while. The fellow approached me, asked me where I was heading to and warned me of the dangers of walking alone on that road. As usual, I made up some stories about how comfortable and safe I was feeling at the moment, but I ended up getting a ride to the house.

Contradicting my paulistana luggage and the opinion of my ride driver, the road showed to be perfectly safe in the following days. With the ongoing blackouts in the city (a subject for another text), walking in total darkness became a routine in Kampala. Sometimes it is quite difficult for me to disassociate from the reality I had in São Paulo, fearing for my belongings, for my life and for the life of people around me. But so far, East Africa has given me lessons of social interaction and a wealth of thoughts for my research on poverty.

I had handpicked my Couchsurfer. In his profile, he described himself as a specialist in the TIC sector for development and worked in several projects in Uganda trying to develop platforms based on mobile technology for social development. I was not really surprised with the couple that hosted me, but when I woke up the next day I was invited by a person related to them to visit Namuwongo, the key slum for my research in Uganda, for a documentary filming.

I did not think twice, I took a boda-boda (a motorcycle-taxi) to Namuwongo and met with the Film4Change team. I would be watching from distance the entire filming of a documentary about the slum to be conducted by a team from Uganda , which was trained the year before by an international organization. To me, this was an opportunity to observe the environment and make initial contacts for the following weeks.

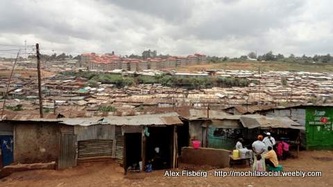

At the gate, we left behind an Italian organization of International cooperation and we walked to the entrance of what is considered as the slum. Two different worlds. After crossing the railroad that separates the “city“ from the slum, we climbed a small hill covered by trash until we reached the narrow entrance of houses on the dirt soil. No clusters in this area. It was possible to watch the endless movements of people from one side to the other, running small businesses or busy with handcrafts on the so-called pavement.

The documentary producers were busy trying to redo a drowning scene that took place weeks before our visit, but the movement and the composition of that scenery would, at any day, serve as subject for another hundreds of videos, studied and considerations. But obviously, there are not many people interested in that reality. The crowd of curious people was justified: muzungos, professional movie cameras, tripods, microphones and breaches of protocol with the elected local community leader.

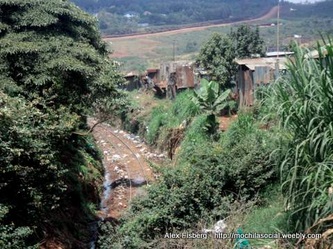

Facing the creek that separates the community and a piece of land covered with small plantations, young people were representing a routine scene of the region: the drowning of a youngster or of a child, trapped by the unstable and swampy land, in the backyard of the houses in Namuwongo. The children that followed us seemed not to care about it – or were not aware of the risks– and walked along barefoot, stepping on feces, open sewerage and trash, a lot of trash.

Women show up from the middle of the forest carrying long stems of sugar cane on their heads. Slowly they cross the murky waters that reach their bellies, heading to the side where I stand, the safe side. Without losing their balance – and with no help whatsoever – they reach the not-so stable ground, and continue carrying their harvest heading to the slum. One of the pieces of sugar cane is handed to the children, who violently bite it and devour the unpeeled sugar cane.

The adventure comes to an end when the filmed scene finishes, and the community slowly returns to their daily routine. The same group of children that showed me the way in now takes me to the opposite direction, to the way “out”. The sun was scorching throughout the whole day spent in Namuwongo, but now, thunders bring the threat of strong rain. How would the life be in a slum – with no sanitation and located at the edge of a filthy creek - when it rains?

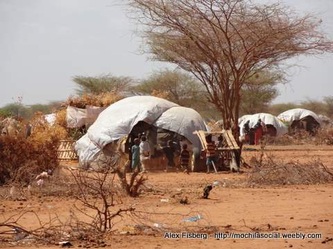

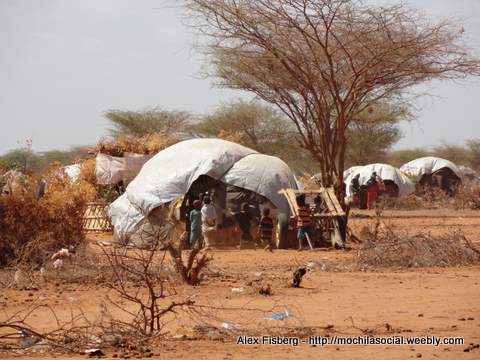

In the last week of September, Dadaab, the already most famous refugee camp in the world won another title: third largest city in Kenya, overcoming the city of Kisumu, next to the border with Uganda. With thousands of Somalis arriving every day, escaping the draught and a violent government self-imposed by the Al Shabaab group, the refugee population in the city exceeds already 430.000 inhabitants.

There is no doubt that this is a unique city. It is a mix between temporary and the challenge of getting settled in a region impacted year after year by strong draughts. This dynamics leads the different populations of the region to have, to say the least, interesting relationships. More than 35 international agencies work in the area, and they have their own complex, protected and distant-enough refugee camps. Kenyans, muzungos and even Somali refugees work at the complex, based upon an incentive policy to reabsorb that population (the so-called incentive worker).

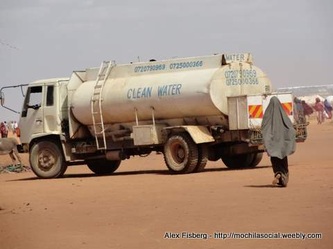

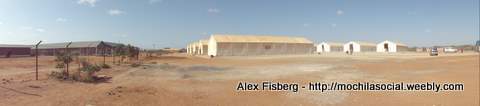

During the 80s, the camp was designed to shelter up to 90 thousand people. Today, it bears 5 times more of the anticipated capacity, and new expansions and new camps are being seasonally planned and built to receive the increasing flow of Somalis. The services offered to the refugees lead, many times, to troubled relations of the local community (host community) with the government and the humanitarian-aid agencies. After all, while those who have refugee status receive all the necessary goods for free, such as water, cooking devices, blankets, and aid to build shelters, the local Kenyan population, who is o affected by the draught, struggles to survive and to receive any available leftovers from the refugee camps.

Driving a 4x4 we crossed the sand road opened in the middle of a desert landscape towards extension “A” of the IFO camp, where we would have our first contact with the local struggling Somali population. Our first stop was at a huge WFP warehouse complex, where readymade food was distributed to the refugees by means of other agencies. WFP is in charge of distribution in Dadaab, and has been using different products trying to ensure nutrition for those people. One example is the Plumpy Nut, a type of caloric-powder bomb, widely distributed in different versions in Dadaab camps.

It is impossible to deny the need for emergency care for the refugee flow that arrives daily to the camps, but after more than 20 years, some things could be done differently. The political plot of the region benefits neither the local population nor the refugee community. On one hand the Kenyan government has its eyes quite open to the challenges, but also to the opportunities that a humanitarian crisis in the neighboring country may generate. On the other hand, Somalia, which does not have a well–structured government, is fighting the extremism of a radical group such as Al Shabaab, but receiving only an uncompromising support from the so-called “International Community”.

There is a lot of potential in the region between the far east of Kenya and Somalia. Despite the draughts, it is possible to find natural underground water sources or find them at viable distances allowing for the construction of ducts and pipelines for irrigation. After all, there is an unremitting transportation activity of food supplies, so it would be very plausible to turn the refugee camp into a small-plot camp of productive land. The investment would not be much different from the figures spent today in the region and, in the case of a resolution in Somalia, the refugees could return to their lands with some survival techniques and even some income.

The main problem is the lack of stability in the region and the crisis solution being just an “organized Somalia”. The Somali population has nowhere to resort to in their own territory, since the FRA, the group opposing Al Shabaab, still lacks enough strength to take the power (and according to the representative of a French organization that works on the other side of the border, it is still unknown if they really are the “good guys” of the region).

In one of the schools built at the exit of the IFO camp, the Principal shares some of the challenges he faces there: high rates of girls abandoning school because they have to give priority to the work at home for the survival of the family ; student/teacher ratio exceeding the hundreds, as opposed to the recommendation of the Kenyan Ministry of Education, which is 1-40; one book for every 72 children; and the constant challenge of incorporating newly-arrived orphans, who come to the school for a second chance.

The objective is not to settle those children there. The goal is to prepare them for the national and international tests in universities, mainly the private ones, where there is less red tape. Therefore, says the Principal, some of the students that managed to attend Kenyan or even Princeton Universities become role models for the other children, and many times those youngsters return to the region to somehow contribute and give back to the community.

We did not have any surprises walking along the camp: dozens, if not hundreds of children surrounded us. With startled looks, different from those who were simply interested in what is different, they watched us from a safe distance, avoiding direct contact. The bravest ones came closer, and were received by us with smiles and attempts of physical contact.

In a few minutes, dozens of children were reaching out their hands for a “high-five”. As if it were the first time in their life they participated in some type of playful games, they were divided between those who laughed and those who ran away fearing what would come next. Their upset smiles, many times hidden under a piece of cloth, would open their faces, for the first time, for the experience of playing something different than pushing water gallons or following the steps of an adult. At the end, obviously, children are just children, and deserve nothing more that everything we have to offer.

One of the reasons I went to Dadaab was to try, once again, to understand the parallel of the “temporary-definitive” phenomena. Such phenomena was also observed in most of the slums I visited, where a situation that was supposed to be temporary, a transition phase between a negative situation and the opportunities for a better life, ends up becoming a burden for an entire generation or even more. Of course, in the case of Dadaab there is a clear involvement of two nations and an endless number of external players coming from all parts of the globe. So what is in fact, the difference between a slum in Nairobi inflated by Sudanese immigrants, and a slum in Kampala, with a Congolese majority? They are also suffocated by international aid of the most varied flags and stuck to a “temporary-definitive” logic and vision.

This text was kindly translated by Tania Cannon. Thanks!Unbelievable, but I woke up with the noise of rain. That’s right, a reasonable strong rain, so close to the region affected by the draught. I spent a few minutes observing the pools forming on the pavement, dragging mud from one side to the other. I counted the drops, measured as much as I could the amount of water falling, and squeezed my thoughts trying to understand what was going on in the region. Obviously it was too early to understand anything .

Getting a ride was much more complex than I thought. We went to the specific place where the international agencies used to meet on Sundays to assemble a convoy with security escort to Dadaab. There, Muzungos, Kenyans and Somali refugees take turns in cafés, in one of the fancies hotels in town, and talk about how to save the world (according to their own perspectives). To us, the primary interest was still our ride (since coffee was expensive and the conversations were, let’s say, weird)

We asked all the people, all the cars, we negotiated with all the taxis and checked all the possibilities with the buses. We received an endless number of “no’s”, other excuses, exorbitant prices and impossible bus schedules on that same day. At least we had the opportunity of meeting a very nice American woman, working for CARE, planning three additional expansion units in one of the refugee camps in Dadaab.

Defeated we walked back towards our hotel. The plan was to take the bus heading to the city of e Dadaab at 7:00 am the following day. However, a huge truck from the World Food Program, carrying what appeared to be food, crossed our way. My contact in Dadaab belonged to WFP, so I decided to try talking to the driver. I think that the cabin was at least 3 meters high, and it was a challenge to listen to him– to understand him. But I heard the essential: “I am heading there! Now. Get in”. Without thinking twice we climbed to the door and got in the truck.

The truck was carrying wood structures to be used as support to the food to be distributed. They were over 30 meters long and, thanks to our luck, they provided us a very confortable space to travel. The trip was not easy. Besides the physical pain from being tossed several times against the ceiling, against the wall, or against the other bodies in that cabin, what really hurt us was the landscape.

First of all, the beauty. A place like I’ve never seen before. The road is an opening in the white sand in the middle of dry and short bushes, some of them still boasting the green of the previous and now so distant rainy season. The orange from the road banks, of the apparently fertile dirt, waits for some sips of water to develop its full potential. Water that is not coming. And apparently won’t come.

The thirst is more evidenced by the several animal carcasses spread on the road. That simple: in some moment, they gave up on life and stayed there. Until they dried up, they discomposed. The image of vultures eating a carcass is unreal; not even vultures dare to wonder by this dry and deserted land. But many do not have the option to fly away. Along the road, children, adults and veils balance yellow galloons in the air, waiting for the water quota distributed daily. Sometimes distributed by the Kenyan government, and sometimes by International agencies. And sometimes, the water simply does not show up.

A military checkpoint. Surrounding it, a camp with hundreds of people, tents and some activity going on. There, at least, the residents of the region know that some infrastructure will appear. With no much hope, even the officers seem to be tired. The region is considered dangerous, and there is a constant fear of an invasion or infiltration of the Somali group, the Al Shabbab. The inspectors did not even bother with our presence in the truck, and in a few minutes we were back to the loneliness of the road.

A full moon was slowly coming down on us. A few meters before the entrance to Dadaab we stopped: for the driver this was an opportunity to fix something in the truck; for me, this was the last sigh before entering the complex world of Dadaab. On one side, the sun set, on the other, the full moon. And, as usual, both totally ignoring our structural and political problems.

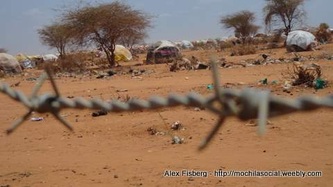

We arrived to the city of Dadaab. On one side, the gates of the complex of the 35 organizations that work in the region. On the other side, a diverse “local” population, separated by barbed wire and with security to concern every foreigner. Our entry in the “safe” complex was denied. Apparently tonight all the available accommodations from the international agencies were occupied. At the guard booth we were considering all the possibilities except for the one that ended up happening.

Fred introduced himself as the person in charge of the complex security. A lie. But, oh well, he told us that the “house” was full and the accommodations outside the complex were also full. He made a suggestion: why don’t you sleep at the police station? It would be safe, “confortable” and convenient. He failed to tell us that it would be very expensive.

We walked along the streets of the city, no further than 1 kilometer from the gate. We did not draw much attention due to the darkness, but even though we found the small military base, filled with soldiers armed with machine guns and showing a concerning lack of care. We sat down. Every minute or less a new soldier looked at us, asked something to his colleagues and then greeted us with a smile that could be seen in the darkness.

We got to the middle of the way, between the improvised sentry box and the possible accommodations. We stopped to answer confusing questions and receive information on the conditions of our stay. All along, among uniformed military and guys imposing respect just because of their stance, a very drunk fellow followed us within the barracks, mocking and being mocked by the armed citizens.

The bedroom door opened and we entered a movie. Undoubtedly this scene had been produced by a horror movie (or comedy) screenwriter. The walls were stained with infiltration and filled with posters and signs that let anyone wondering about the character of the tenant. Some chests spread out on the floor, a club on the wall, a rescue patrol t-shirt that carefully thrown on the floor weeks ago. The beds were even more caricatures: the protection net against mosquitos on one of them was an invitation to keep our distance; on the floor, a mattress carried an entire ecosystem of plants and animals under a fuzzy blanket of a terrible esthetic sense.

We dropped our things, used the bathroom (we are still not sure if we relieved ourselves in the right place) and went out to the bar at the barrack. The welcome letter read the following: “Please do not consume alcohol when wearing the uniform or bearing weapons”. Next to the sign, approximately 100 guys huddled around thousands of beer bottles spread out all over, screaming, drinking and doing who know what.

-Alex!

When I turn I see our best friend Fred and his companions sitting down, smiling and drinking all the money they extorted from us. That was not the company we were looking for, but we could not avoid it and had to join them. At the bar, only one choice of food and a lot of alcohol. As the mixture was not attractive, we went for a beer, but as its temperature was boiling we decided to shorten the night and go to bed. The next day would be inside the complex and we were trying to get ready for that experience in Dadaab.

Sitting in the uncomfortable chairs of the office, we were waiting for the bad news. Why would the Kenyan Government issue a permit to visit the refugee camps in Dadaab, Northeast region, close to the Somalia border, to three young fellows with no reasons for that? We were told that the process to receive the authorization letter would take, at least, 14 days to be issued. This fact contradicted the procedure sent by UNHCR (The United Nations agency which deals with refugees) but mainly, our plans of traveling the next day.

Everything in that room smelled as a certain “corruptive potential”. The information and answers provided to us seemed to be more an opening for a proposal – or a request – for bribe. We were not willing to be corrupted, but it was clear that our situation was quite delicate: if the permit was not issued that day, we would travel without it A quite offensive question: what tribe my Kenyan colleague belonged to. Frowns aside, such information here in Kenya still bears some influence in the daily interactions. After all, depending on who you are, things happen or not around here.

Apparently the officer was making an exception for us. He made a point of making it very clear that he was “facilitating” the process for us, “going around” the bureaucracy and doing us a favor. Fact: this could only be hints for money given on the side. Instead of taking the previously stated two weeks, we would have the documentation in just three hours. When it was time to receive the documents, the tension of being interrogated and forced to give some bribe was only in our disturbed minds. The process was totally clean (at least as far as we could understand it).

Another major challenge was to ask directions to Garissa, the closest city to Dadaab. Just because no one could understand how a muzungu like me would make the effort to take a bus in the Somali region of Nairobi to a totally far away city. Usually, the international agencies working in the region fly in small commercial airplanes, or they have their own vehicles. However, the residents squeeze in the narrow seats of a crowded bus, for a trip that lasts less than 6 hours.

We left the region of Eastleigh, the Somalia in Nairobi. It was amazing to observe the change in the population, less than 15 minutes away from the downtown area. Here, there was a large immigration of Somalis from Somalia and of the so called Kenyan Somalis, from the regions close to the border. A chaotic, muddy market, with moving burkas is the main scenario of this region. In the bus, reading of the Koran, Kefiahs and burkas fight for the narrow space and rearrange themselves in the bumpy road. For a few hours I had the delightful company of a bay to play with, handed to me by a burka, with no further explanations.

The road, lit only by a full moon, was slowly getting emptier and showing only the shadows of dry bushes From time to time, a camp of people living in the middle of nowhere. Huts made of twitched branches, covered by all types of material that could be found in the region, that is, almost nothing. A lost look would now and then find our bus, but in a few seconds we were just a memory.

It was already night when we finally arrived in Garissa. Our plan was to get there at lunch time, enjoy the transition city and rest, so we could travel the next day to Dadaab. We rented the first “room” that we were offered. A brief pause to introduce two characters: a tall, thin gentleman, wearing a kefiah, who did not speak a word of English but would please everybody with his laugh; and a very thin young fellow, with a few teeth in his mouth and whose English accent had been robbed from several interactions in the past.

I had fun with both. First, a theater of mime, smiles, laughs and faces to select a room, a price, and seal a quick friendship with the smiling Arab. Then, a stroll around the almost empty city in search for a Coca-Cola. Along with us, the fellow with no teeth took us to the city’s bar, while repeating the expression “absolutely”, with a mix of heavy British, Texan, Kenyan and Indian accents.

After buying our things (two Cokes and two cartons of milk) we were ready to rest and get our minds ready for the road to Dadaab. But we did not have a ride, UNHCR was not responding to any of our communications and we have not made arrangements for a place to sleep there (Dadaab is not exactly the capital of backpacking tourism). We decided that the next day we would stand in line for a ride.

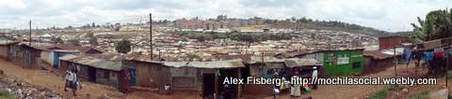

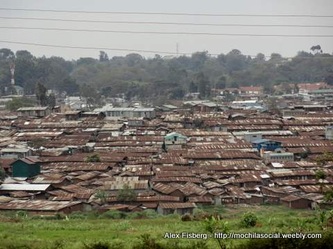

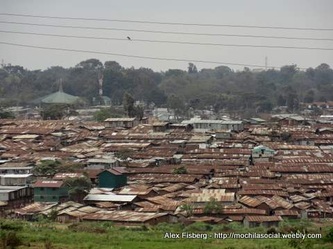

I arrived in Kenya with some specific goals. One of them was to visit the Kibera slum in the suburb of Nairobi. Kibera is famous and considered one of the largest slums in Africa. The figures published by International agencies usually exceed 1.5 million residents, but the Kenyan Census of 2010 accounted for a little more than 170.000 people living in that slum.

I am not really a great fan of numbers and I could care less if they are hundreds, thousands or millions. I believe that the problem there is the lack of infrastructure and equal opportunities for whoever is living in that place. I decided to make my first remote approach. I went with my friend and host Stanley, and his girlfriend Debrah, to a middle-class neighborhood called Langata. From there I could have a better view of Kibera. But the view was not good...

On the left side of the view, the UN-Habitat project, in partnership with KenSup (Kenyan Slum Upgrading Program) which I got to know. My two friends worked at UN-Habitat and participated in part of the project, which unfortunately was considered a failed attempt. The project built new houses for Kibera’s residents, right next to the current complex. However, when the residents moved in they had to pay a rent of 1.000KES, almost twice as much as what they used to pay. Moreover, the recently built apartments could be rented for approximately 15.000KES. Thus, the project beneficiaries either sold or rented their new apartments and returned to the so called slum.

We parked our car at the top of a hill and watched the region. A creek divides the KenSup project from the rest of Kibera. At the end of the complex, there are high-value apartments in the region of Langata. While we ate a sandwich in the car, we discussed the possibility of a local intervention. My friends are trying to start a consulting business for the development of slums and poor neighborhoods, by means of trainings and cooperation with several sectors (NGOs, Government, Universities and the private sector).

On the other side of the complex we got to the main Kibera’s court. Basically, the place is the headquarters of most of the trials in the region. My “surprise”: cement floor, running water, electricity, parking with several well-maintained cars, security and that feeling of a “normal place”. One left turn later the slum starts, no running water, no official electrical connections, no pavements and no planning. The distance between the two realities is physically small, but clearly shows the impact of exclusion in the planning of a city.

If it is possible to bring the infrastructure up to the slum “door”, why wouldn’t those benefits reach the residents? There is a huge list of NGOs and international agencies working with the community in order to empower young men and women, to prevent HIV/Aids, conduct trainings in entrepreneurship, business and microcredit, among other things. But how is it possible to improve the quality of life of those people and develop the region without providing them with the basic infrastructure of the rest of the city?

I am always pondering about this whole social business issue and the “innovative solutions for the poor”. Why do those people, who are currently being considered as poor, deserve different solutions than those that we, “the rich”, have in our houses? Why not start here: offer to the “slum” the same services that are offered to the rest of the city. Obviously, infrastructure is just one part of the problem, but if we compare it to agriculture, the first action is to prepare the soil, then fertilize it, plant a variety of seeds, “irrigate” and then, harvest.

In order to prepare the soil, it is important to ensure that the residents in the region have access not only to water, and electricity, but to health services and quality education as well. This may sound trivial, but it is also important to consider building adequate access roads, in order to develop a relation between the region and the rest of the city and its economy. In this phase, I believe it is also important to conduct a detailed mapping of the community conditions, active leaderships and organizations, status of the ground and presence (at what level?) of the public power.

In order to fertilize the soil it is essential to have children’s education action, empowerment of youth and women and specific trainings. By and large, the important is ensure that the community deficient areas are served by those trainings, but the essential is to find out which tools the community already has and then catalyze them. Instead of approaching a community just looking for problems, the mapping is critical in order to identify the tools, the already existing institutions and “fertilize them”, offering the coordination and cooperation between such initiatives, the public power, the private initiative, and of course, the rest of the civil society.

The initial actions also correspond to planting the seeds. It is important to take into account the “irrigation system” to be applied to those seeds. A follow-up by the leaderships, periodic meetings between the community members and the engaged partners (be them government, enterprises or the civil society). In my opinion, it is important to hold these meetings within the community, in the “soil”, to make sure that all are completely involved in the physical and abstract changes of the region.

The harvest portion is not passive. As soon as the community starts reaping some fruits, it is very important to ensure the access to the markets and services of the rest of the city. And it is also important to work in order to break the region stigma and warrant equal rights in all levels to all the local residents. This could be done by means of the media, exchange projects between the regions, and mainly, by means of a spontaneous media generated by the residents.

I’ve observed that a very common phenomenon that often happens is the exodus of youth and trained leadership from the community. Of course this means, on one hand, the improvement of the quality of life of those people. On the other hand, the region continues suffering from the same problems, receiving more and more people and repeating the migratory cycle: on one hand, the number of people that arrive from the rural or less favored areas to try their luck in the urban clusters is constantly increasing; on the other hand, young people and trained leaderships are abandoning the community.

It is clear that what I drafted here is a theoretical and simplistic description of a slum development project, but I believe it is worth it to highlight that so far, in my observations, there is always a pattern in those regions: a clear division between the city and these “non-places” called slums. If we already have the means to develop those regions as well as the rest of the city, why not do it r?

One of the arguments, which is very valid, is that the services provided (such drinking water, sanitation, electricity and benefits related to the legal property of the land) are still too expensive for those dwellers. As unemployment and underemployment rates are extremely high, even the smallest amounts, if constantly charged, are unaffordable. I believe that one action leads to another: when the quality of life and stability improve, the residents of these communities have more tools to restore and achieve better jobs (together with technical support and specific training).

Everything is important. Access to the right markets, skills that may generate income and livelihoods, participation in qualified networks that can catalyze interesting initiatives, and so forth. However, one cannot take a paternalistic position, which is often observed, saying that “those people” do not have the necessary characteristics to escape poverty. Much to the contratry. I constantly challenge myself to try to imagine how to survive with less than a dollar a day, with no infrastructure, no voice, no support and no reliable institutions, and I always fail in my projections.

People in a poverty situations (because let’s admit, nobody IS poor) are extremely qualified and professionals in the art of surviving in more than adverse situations. Once I heard form an NGO coordinator that those people do not know how to manage a budget and need training; and I wonder how they maintain a house with more than eight children, with no money, no resources. And how come, even though, some of those children attend school, even attend college, find jobs and improve the quality of life of their families. It seems to me that “those people” have some understanding about economics.

What really bothers me is seeing development and underdevelopment, side by side, living together as if they were two different worlds. The solution is clearly complex, but not necessarily complicated. I feel that if we are no managing to find some answers, we need to start asking the right questions.

It was my fault. Once again, it is easier to justify the fact that I was careless than to question this type of situation. “Ah, if I just had acted differently” or “why did I leave my things there” are thoughts that crossed my mind, but I no longer feel anything when an aggression like that takes place. I no longer feel paralyzed, not even surprised. I put up with my loss and think how to go ahead.

I feel wronged, and what hurts me more is not being able to express what I feel. A thief does not ask who we are or what we do. He does not allow for a dialogue and does not give room for arguments. He does not let me negotiate what he can or cannot take away from me. I am sure that if I could have an honest conversation with the person that robbed me, we would come to an agreement. I am not traveling as any other tourist, but it does not matter.

Unfortunately, what has happened would not change. Nothing I do or redo will change my losses. Each item of my backpack was important to me, in different ways. When I was selected as a victim of a robbery, I was only a red backpack in the hands of a Muzungu. Just for the sake of it, I decided to list the inventory of my backpack. And argue, item by item, a simulation of what I would say to the thief. I know exactly what I had in my backpack, and I know the impact that each loss will have on my project. A pitty.

I estimate my financial loss – things that I will have to rebuy and redo – in approximately R$3,000.00. That will likely compromise a relevant portion of my project; I might even have to shorten the duration of the Mochila Social. Taking into account that 90% of the money I had been using came from my savings, and that I never was interested in profits from this project, the situation now has changed.

Inventory:

North Face Red Backpack – The best backpack I’ve ever had. A gift from my parents specifically for this trip, but it went with me to India, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Palestine, Ethiopia and Kenya. As you can see, it was the instrument I used to carry the things that are important to me.

Lumix F265 Camera – The best camera I’ve ever had, but, it is still for sale in the store, and if you want to rob me, do it. But please, in regard to the 4GB memory card, if you wait a minute I can download the pictures taken on Saturday, of the Naivasha Lake, and I can give it to you. Those pictures and videos were not saved anywhere else.

The book “Poor Economics: rethinking the way we fight poverty” – If you give me half an hour I can finish the 42 pages I have left and I will gladly give it to you. I bought this book on Amazon and asked it to be delivered where I was, because there are no books for sale there.

National Pornographic green t-shirt– A gift from my relatives, I put is in my backpack specifically because I was going to my first “safari”.

Hardcover black notebook – It has all my research and learning from my work in India about the impacts of migration on poverty and education. Although I have a computer backup of practically everything, it was a beautiful memory of my learning process. It contained the description of the chapters for a book I thought about writing, several diagrams of a future project. I have everything in my head as well, but if I could I would tear some pages out and would leave you the rest. (Enjoy the Indian postcards that are in the back page)

A patterned trip notebook – A very special person gave it to me. It went with me to several trips. It had parts of research, contacts, and messages of affection. I would have liked to keep it.

An Ethiopian fabric – After more than 2 hours of conversation with a boy named Salam, one of the most well-mannered and potentially most intelligent persons I have ever met, I decided to buy an Ethiopian fabric to keep it as a memento. I was using it to protect my camera. If you insist, you can keep it.

A plaid sweater - It was not quite beautiful, and it was not quite warm. But it was one of the three sweaters I carry in my trip.

U$400, 00 – Money set aside for visas for Tanzania, Uganda, Ruanda and, maybe, Burundi. Also set aside for emergencies. I don’t even have words for it; it was more than 50% of all the money I have.

IPod + Phone + Cable – The device is having issues, it locks up every hour and does not turns itself off. It was a “gift” from my brother and it kept me company during my trips. It is still on sale in stores, you can keep it.

Old passport – I had to renew my passport because it was expiring. It was just a souvenir, with stamps from Israel, India, Jordan, and European countries. I had plans to frame its pages; I would love to have it back.

8GB Pen Drive– The stored information is not important. They are texts that I saved to publish when I had Internet access. I gave my first pen drive to someone, and ended up buying that one for myself. It is still on sale in stores, you can keep it.

“Coexistence” key ring – My father made it. He put a protection prayer in the back and the Coexistence symbol in the front. It was in the outside pocket of my backpack, trying to suggest to unknown people a more tolerant world. I believe you may benefit from it.

Cable/Rope – A sort of a metallic cable for any emergency. It already tied my luggage to some pillars.

Cell phone charger – I was so happy because I bought a cell phone that served also as a modem for the Internet. Now, with no charger, I can’t even use my cell phone. I will buy another one, but if you don’t have the same cellular, why would you need the charger for?

Toothbrush and paste, scissors, deodorant, body and anti-mosquito repellent spray

Hamsa, a symbol of protection – Pink, in acrylic, a protection prayer engraved. It was also a gift from my parents, a good keepsake from home. I would like to have it back.

Marker, mechanical pencil, black pen and a pen with the Weitz Center logo

A green Decathlon towel – The best towel I’ve ever had, a “gift” from a great Brazilian girlfriend when she left India. I would like to return it to her someday....

3s Mochila Social Plates – A small gift made by my father, with the project site and logo. The idea was to give those plates to important people throughout my trip. Apparently you are quite important...

An Ethiopian phone SIM Chip– I was keeping it as a souvenir and also in case I needed to go back to the country.

Blue LED flashlight – A farewell gift from Israel, from the family that harbored me for 2 months without asking me almost any questions. They also gave me a wallet to use inside my underwear, and thanks to them I did not lose my passport or the rest of my money (which is not much right)

A birthday card from my uncle and aunt – A card given to me by them, in advance for my November birthday, in case we would not see each other. A piece of cardstock with lots of affection and meaning. I would like to have it back....

Sunglasses – They were fake, bought from a kind of street vendor in Sinai...

An Arabic page marker – My favorite page marker, in the shape of a Sunni Arab wearing a kefiah.

Green Shorts with a hole in the leg – My favorite shorts. Truthfully, the only bermuda shorts I took to India and I wore it from the beginning to the end of my trip. I will have at least a lot of memories of it, since I am wearing it in almost all the pictures.

As you can see, most of the things are of value only to me.

It all started with a phone call. And the telephone, extracted from an n old and outdated spreadsheet, which connected your name to another organization, another slum. That’s how I meet Ezequiel, a potential young leader of the Mathare slum, a few kilometers away from Korogocho.

We sat at a café somewhere in Nairobi to chat before hopping into a Matatu heading to the community. We were analyzing each other. On his side, why in God’s name, a muzungu like me would come closer to a slum? Probable answer: bored with my plentiful life in Europe, I decided to help the poor. On my side, I just wanted to make sure that he was someone with access to the community and able to freely represent – or access – Mathare.

After a few minutes chatting, we adjusted to reality. He understood that my objective was learning, researching, and my intention was to contribute with ideas and contacts from other organizations, at least for a while. On my side, I felt safe that, despite not being currently involved with any organization, the self-defined job as a free-lancer sounded interesting. We talked, I paid for the coffee and we left.

On the way we talked about some ongoing projects, such as the apparently gruesome RYP (Rehabilitation Youth Program) a youth center called Luwaku and a garbage collection cooperative, also carried out by youth of a community called One Love. So many projects related to youth. My question was answered: he was born and lived for over 20 years in Mathare. He knows everyone.

We walked along the asphalted and commercially busy side in the outskirts of the slum. On the way, several signs referring to the international cooperation projects between the Germans and the Kenyan government. In one of the parts of slum (Mathare 4A), a German initiative tried to renovate some houses. It turned zinc shacks into cement houses. Until today it is clear to see the impact of such intervention, but the project was interrupted due to the tribal violence after the 2005 elections.

The region has two well-defined areas (and many others that are undecipherable): on one side, asphalt, 3 to 6 story buildings, public utilities (deficient, however present) and an atmosphere of “normalcy”; some more steps through the landfill, once again a bridge and we get to a second area, apparently with no planning, no infrastructure, e no presence of the public power. But a lot of people living there.

The houses are distributed along one creek and end where a second creek starts. During the rainy season (according to the residents, during practically any rain) the two creeks merge, flooding the narrow land strip that has more than 200 houses. On one side, called Ndoya, a school, blockhouse style, was built and it is one of the most stable constructions in the area, avoiding the constant flooding of the creek. I got used to the smell suffocating odors of open sewerage, but I confess I was knocked out by the smell coming out from the narrow pathway at the edge of the creek.

Surrounding the school the houses are not very well designed and are constantly flooded. The dirt ground, totally flooded and covered in insects is the place for plays and nice smiles of hundreds of slum children. A symphony of “how are you?” comes from the cheerful voices of the little ones, but in my mind the answer is not as positive: how am I? I am trying to find out some feeling that would justify so much neglect and abandonment, so close to the “rest of the civilization”.

The surrounding buildings consider this part of the slum– including its dwellers – a major landfill. Every day they toss from their windows the garbage from their houses, with no regard to the final destination of that waste. But we, here below, know exactly the impact of such lack of respect: piles and more piles of accumulated trash being collected daily by some of the young members of an organization called One Love. However, the amount of trash and the way it is disposed of hinders any nearly acceptable result.

We crossed to the other side of the community, and we arrived to the second creek. A weird invitation: I was invited to see the collective latrines of the slum. I squeeze sideways through a wooden wicket and barbed wire and I reach the creek’s edge. Here, two small houses made of twisted metal and wood serve as a refuge to satisfy the most basic physiological needs of the residents. And obviously, from there the waste goes to the same creek. The background landscape is filled with trash, plastic bags and buildings that surround this part of the slum.

Watching the brown-bluish water that practically does not move, an unpleasant sight. At first we thought it was a doll, a toy that children play with and learn how to care for another being, even if just playing. But it wasn’t. With only one arm and a part of the body outside the area a newly born (or better, an aborted baby) laid there, on a pile of trash that formed an island in that insensitive landscape. I was reluctant to take a picture, but I registered the image. From far away, with no expression and a pain hurting somewhere in my being.

Talking with the residents we understood that this is something that repeats itself very often, not only here. Abortions are carried out through illegal and dangerous procedures, and the aborted fetus is discarded. Just like that. On the other side of the fence a local church building. According to Ezequiel, the marriage of his sister will be celebrated there the next day. And that’s how I took the baby’s image away from my head and replaced it with a romanticized scene of the union between two strangers. Just like that.

I got into a common matatu inside Nairobi, but destiny waited for us a few kilometers from the Kenyan capital. Our transportation dropped us off on an asphalted street, but from there on the path was a dirt alley. An active market took over the scenario, but we were walking on an extremely uneven land, full of cracks and holes, where hundreds of people and some motorcycles circulated. The alley, approximately 500 meters long, is the last existing connection between the presence of the public power and the Korogocho slum.

The end of the alley opens up to an open field covered in trash. A creek separates the open field from the beginning of the residential area, and in an exposed sewerage pipe children play of hanging above the water. We crossed a less than 1 meter-wide bridge and arrived to the main street where the slum begins. We walked on, surrounded by alert eyes and a greeting from a Muzungu that passed by. A left turn, going by several clotheslines, and we at last arrived to the office of the organization I was going to meet with: SUFTA (Societies United for Transformation in Africa).

I was greeted by John, one of the organization founders. According to him, SUFTA was founded by some young people who were born and raised in the community. I asked him to explain how the organization worked and about the ongoing. I admit: I was dumbfolded by the explanation. He talked about strategic planning, social business, empowerment of young people and women, community social development, holistic approach and other terms that so much used today by NGOs and international agencies. I decided to ask a sensitive question and I was quite impressed by the answer.

-John, where does all this knowledge come from?

He answered me with a shy smile. The organization founders are university students who graduated in administration, economics, and community development. It was interesting to check some data that state that a large number of young Kenyans currently attend the universities in the country. And they specifically decided to use the acquired knowledge to return to their community of origin and make a difference. This was much better than the answer I was expecting, regarding some type of a standardized training provided by some organization.

We discussed a new project of legalizing marriages as a way to reduce domestic violence and make men and women more sensitive about the commitment of starting a family. And, at the same time, IT projects, prevention of HIV/AIDS and malaria, development of small business and psychological support are part of a weekly agenda in the community. An international volunteer of AIESEC was also there, teaching English for the local children.

It is estimated that 120,000 residents live in the Korogocho community, and 70% of the population are 30 years old or less. It is considered the fourth largest community in Nairobi, behind Kibera, Mathare (neighbor community) and Mukuru Kwa Njenga. It is an illegal settlement founded in the 80s, by a majority of immigrants coming from rural areas and even Tanzania. The land is divided and more than half of it belongs to the State and the rest belongs to a private owner. There is no presence whatsoever of the public power in the region, and water and electricity distribution is illegal. Most of the water in the region comes to some water tanks and it is redistributed by middlemen, thus raising the price considerably (according to John, the water quality is very poor).

The presence of the government can barely be noticed when walking along the community streets. On the contrary, it is quite easy to realize where the government presence ends, a little before the access bridge to the slum. On one side, running water, public lighting and how can we say it, aligned streets. On the other side, abandonment in the midst of dirt narrow alleys and improvised houses made of metal sheets and mud.

SUFTA supports two local businesses as a way of pursuing its financial sustainability: a candle factory and a tomato plantation. The profit is used to maintain the office overhead and the activities in the community. Although they still depend on a monthly donation given by a British citizen, who “adopted” the project, the organization founders and directors are looking for ways of being financially independent to develop their activities.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed