This text was kindly translated by Michelle Fidelhoc. Thanks!

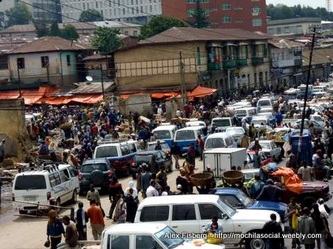

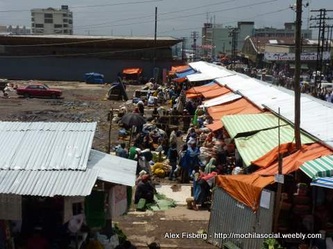

We were waiting for the bus like everyone else. Me and a Spanish friend had come down from our first bus, a ride of more than 10 hours, and were then waiting, sitting in an tree trunk, in the midst of a light rain. All of the gazes were focused onour strange presence in that village, making a route that is not so common for farengis to do. Anyway, we had the rest of the way by land ahead of us and we needed a "ride".

We tried to enter the first bus that passed, but were denied permission. Not that there weren’t vacant seats left, but the driver made it clear on some sort of body language that he couldn’t take us before the intermediary defined our differential price. After a series of evaluations, a young man warned us that, if we wanted to catch that bus, we should reserve our seats first, paying four times more than the rest of the passengers.

Suddenly, a light came up: a rich-looking Ethiopian citizen who spoke excellent English was doing the same route as us. He offered to help as our intermediary, but we soon started to realize that the light was not as bright as we had thought. He was actually negotiating the seats of those who were already inside the bus, offering more money and forcing them to leave the bus. We made it clear to him that we disagreed with what he was doing, and we didn’t mind waiting for the next bus and traveling "normally".

Everyone left the bus and a reorganization of seats began. First, our "friend" took the front seat, which is considered to be the best. Then, the boys pushed us into the bus. Right after that, all of the people that were there before us had to squeeze themselves in the remaining seats. As we sat, the prices were put on the table: 20 Birr for everyone, 40 Birr for our friend and his special seat, and Birr 60 for two farengis that can not argue directly with the driver.

Seated, I complained about having a seat that I did not deserve. I complained also for paying three times the price of the trip. And discussed with our "friend" about all that reorganization of seats being simply wrong. Apparently, after some laughs, it became clear that morality and ethics were not a concern for that gentleman, who had just returned from a training for international agencies in Germany. For me, they were. We threatened to get off the bus, but were warned that the procedure would repeat itself in any other mean of transportation that we tried to take.

Meanwhile, among the crowd that watched us, one face was static. His clothes were torn. That is no new in a place where so many children are covered with only a few rags. The adults also seemed to be wearing the same piece of clothing that they were in weeks. The brownish color of the dirt and the wear prevailed over all the other colors, and the smell permeated the atmosphere of the mini-van.

I noticed him looking at me from the moment I got off the first bus. I, of course, could understand that I was new to him. I was impressed with the amount of time he spent watching me. Actually, in Gashena, a village 62 kilometers from Lalibela by land, there is little opportunity for activities, be it economic or social. His black skin was very dark and smooth, but it was covered with dust. His dry lips, almost motionless, outlined from time to time a half-smile.

I did not smile. I was furious with the reorganization of the seats and with hearing the excuse I hate the most: "This is Africa". My gaze was fixed on a boy outside the mini-van. Our eyes didn’t leave each other for a second, and I wondered what he was thinking. Wrapped in a cloth that was once purple, there he was, static, maybe with a head full of thoughts, maybe not.

I don’t know what happened. My chest tightened. My eyes moistened. I was embarrassed. There I was, after more than a year of traveling, shedding tears for some kid in a village somewhere in the middle of Ethiopia. I didn’t hide my tears, but they were unnoticed. The salty water that ran down my cheek was a response for what I’d seen in the last days. And I considered myself so strong and prepared to observe and reflect on Poverty.

There was something in the complexity of that whole scene that made me lose my composure for a moment. I did not cry of pity or sorrow. I did not cry of hatred or anger. I cried, for I did not understand. I cry because I still do not understand how it is possible that two very different worlds live together in such harmony. I cried, but I no longer cry.

We were waiting for the bus like everyone else. Me and a Spanish friend had come down from our first bus, a ride of more than 10 hours, and were then waiting, sitting in an tree trunk, in the midst of a light rain. All of the gazes were focused onour strange presence in that village, making a route that is not so common for farengis to do. Anyway, we had the rest of the way by land ahead of us and we needed a "ride".

We tried to enter the first bus that passed, but were denied permission. Not that there weren’t vacant seats left, but the driver made it clear on some sort of body language that he couldn’t take us before the intermediary defined our differential price. After a series of evaluations, a young man warned us that, if we wanted to catch that bus, we should reserve our seats first, paying four times more than the rest of the passengers.

Suddenly, a light came up: a rich-looking Ethiopian citizen who spoke excellent English was doing the same route as us. He offered to help as our intermediary, but we soon started to realize that the light was not as bright as we had thought. He was actually negotiating the seats of those who were already inside the bus, offering more money and forcing them to leave the bus. We made it clear to him that we disagreed with what he was doing, and we didn’t mind waiting for the next bus and traveling "normally".

Everyone left the bus and a reorganization of seats began. First, our "friend" took the front seat, which is considered to be the best. Then, the boys pushed us into the bus. Right after that, all of the people that were there before us had to squeeze themselves in the remaining seats. As we sat, the prices were put on the table: 20 Birr for everyone, 40 Birr for our friend and his special seat, and Birr 60 for two farengis that can not argue directly with the driver.

Seated, I complained about having a seat that I did not deserve. I complained also for paying three times the price of the trip. And discussed with our "friend" about all that reorganization of seats being simply wrong. Apparently, after some laughs, it became clear that morality and ethics were not a concern for that gentleman, who had just returned from a training for international agencies in Germany. For me, they were. We threatened to get off the bus, but were warned that the procedure would repeat itself in any other mean of transportation that we tried to take.

Meanwhile, among the crowd that watched us, one face was static. His clothes were torn. That is no new in a place where so many children are covered with only a few rags. The adults also seemed to be wearing the same piece of clothing that they were in weeks. The brownish color of the dirt and the wear prevailed over all the other colors, and the smell permeated the atmosphere of the mini-van.

I noticed him looking at me from the moment I got off the first bus. I, of course, could understand that I was new to him. I was impressed with the amount of time he spent watching me. Actually, in Gashena, a village 62 kilometers from Lalibela by land, there is little opportunity for activities, be it economic or social. His black skin was very dark and smooth, but it was covered with dust. His dry lips, almost motionless, outlined from time to time a half-smile.

I did not smile. I was furious with the reorganization of the seats and with hearing the excuse I hate the most: "This is Africa". My gaze was fixed on a boy outside the mini-van. Our eyes didn’t leave each other for a second, and I wondered what he was thinking. Wrapped in a cloth that was once purple, there he was, static, maybe with a head full of thoughts, maybe not.

I don’t know what happened. My chest tightened. My eyes moistened. I was embarrassed. There I was, after more than a year of traveling, shedding tears for some kid in a village somewhere in the middle of Ethiopia. I didn’t hide my tears, but they were unnoticed. The salty water that ran down my cheek was a response for what I’d seen in the last days. And I considered myself so strong and prepared to observe and reflect on Poverty.

There was something in the complexity of that whole scene that made me lose my composure for a moment. I did not cry of pity or sorrow. I did not cry of hatred or anger. I cried, for I did not understand. I cry because I still do not understand how it is possible that two very different worlds live together in such harmony. I cried, but I no longer cry.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed