This text was kindly translated by Tania Cannon. Thanks!Unbelievable, but I woke up with the noise of rain. That’s right, a reasonable strong rain, so close to the region affected by the draught. I spent a few minutes observing the pools forming on the pavement, dragging mud from one side to the other. I counted the drops, measured as much as I could the amount of water falling, and squeezed my thoughts trying to understand what was going on in the region. Obviously it was too early to understand anything .

Getting a ride was much more complex than I thought. We went to the specific place where the international agencies used to meet on Sundays to assemble a convoy with security escort to Dadaab. There, Muzungos, Kenyans and Somali refugees take turns in cafés, in one of the fancies hotels in town, and talk about how to save the world (according to their own perspectives). To us, the primary interest was still our ride (since coffee was expensive and the conversations were, let’s say, weird)

We asked all the people, all the cars, we negotiated with all the taxis and checked all the possibilities with the buses. We received an endless number of “no’s”, other excuses, exorbitant prices and impossible bus schedules on that same day. At least we had the opportunity of meeting a very nice American woman, working for CARE, planning three additional expansion units in one of the refugee camps in Dadaab.

Defeated we walked back towards our hotel. The plan was to take the bus heading to the city of e Dadaab at 7:00 am the following day. However, a huge truck from the World Food Program, carrying what appeared to be food, crossed our way. My contact in Dadaab belonged to WFP, so I decided to try talking to the driver. I think that the cabin was at least 3 meters high, and it was a challenge to listen to him– to understand him. But I heard the essential: “I am heading there! Now. Get in”. Without thinking twice we climbed to the door and got in the truck.

The truck was carrying wood structures to be used as support to the food to be distributed. They were over 30 meters long and, thanks to our luck, they provided us a very confortable space to travel. The trip was not easy. Besides the physical pain from being tossed several times against the ceiling, against the wall, or against the other bodies in that cabin, what really hurt us was the landscape.

First of all, the beauty. A place like I’ve never seen before. The road is an opening in the white sand in the middle of dry and short bushes, some of them still boasting the green of the previous and now so distant rainy season. The orange from the road banks, of the apparently fertile dirt, waits for some sips of water to develop its full potential. Water that is not coming. And apparently won’t come.

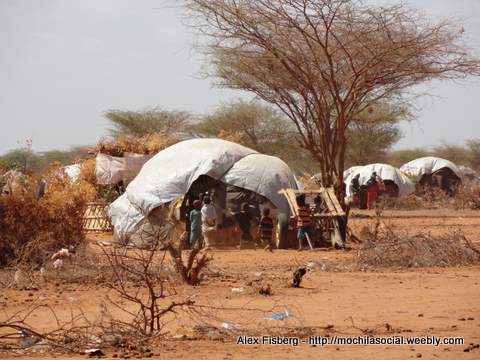

The thirst is more evidenced by the several animal carcasses spread on the road. That simple: in some moment, they gave up on life and stayed there. Until they dried up, they discomposed. The image of vultures eating a carcass is unreal; not even vultures dare to wonder by this dry and deserted land. But many do not have the option to fly away. Along the road, children, adults and veils balance yellow galloons in the air, waiting for the water quota distributed daily. Sometimes distributed by the Kenyan government, and sometimes by International agencies. And sometimes, the water simply does not show up.

A military checkpoint. Surrounding it, a camp with hundreds of people, tents and some activity going on. There, at least, the residents of the region know that some infrastructure will appear. With no much hope, even the officers seem to be tired. The region is considered dangerous, and there is a constant fear of an invasion or infiltration of the Somali group, the Al Shabbab. The inspectors did not even bother with our presence in the truck, and in a few minutes we were back to the loneliness of the road.

A full moon was slowly coming down on us. A few meters before the entrance to Dadaab we stopped: for the driver this was an opportunity to fix something in the truck; for me, this was the last sigh before entering the complex world of Dadaab. On one side, the sun set, on the other, the full moon. And, as usual, both totally ignoring our structural and political problems.

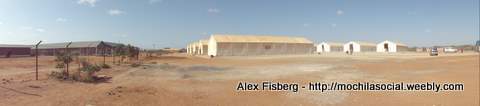

We arrived to the city of Dadaab. On one side, the gates of the complex of the 35 organizations that work in the region. On the other side, a diverse “local” population, separated by barbed wire and with security to concern every foreigner. Our entry in the “safe” complex was denied. Apparently tonight all the available accommodations from the international agencies were occupied. At the guard booth we were considering all the possibilities except for the one that ended up happening.

Fred introduced himself as the person in charge of the complex security. A lie. But, oh well, he told us that the “house” was full and the accommodations outside the complex were also full. He made a suggestion: why don’t you sleep at the police station? It would be safe, “confortable” and convenient. He failed to tell us that it would be very expensive.

We walked along the streets of the city, no further than 1 kilometer from the gate. We did not draw much attention due to the darkness, but even though we found the small military base, filled with soldiers armed with machine guns and showing a concerning lack of care. We sat down. Every minute or less a new soldier looked at us, asked something to his colleagues and then greeted us with a smile that could be seen in the darkness.

We got to the middle of the way, between the improvised sentry box and the possible accommodations. We stopped to answer confusing questions and receive information on the conditions of our stay. All along, among uniformed military and guys imposing respect just because of their stance, a very drunk fellow followed us within the barracks, mocking and being mocked by the armed citizens.

The bedroom door opened and we entered a movie. Undoubtedly this scene had been produced by a horror movie (or comedy) screenwriter. The walls were stained with infiltration and filled with posters and signs that let anyone wondering about the character of the tenant. Some chests spread out on the floor, a club on the wall, a rescue patrol t-shirt that carefully thrown on the floor weeks ago. The beds were even more caricatures: the protection net against mosquitos on one of them was an invitation to keep our distance; on the floor, a mattress carried an entire ecosystem of plants and animals under a fuzzy blanket of a terrible esthetic sense.

We dropped our things, used the bathroom (we are still not sure if we relieved ourselves in the right place) and went out to the bar at the barrack. The welcome letter read the following: “Please do not consume alcohol when wearing the uniform or bearing weapons”. Next to the sign, approximately 100 guys huddled around thousands of beer bottles spread out all over, screaming, drinking and doing who know what.

-Alex!

When I turn I see our best friend Fred and his companions sitting down, smiling and drinking all the money they extorted from us. That was not the company we were looking for, but we could not avoid it and had to join them. At the bar, only one choice of food and a lot of alcohol. As the mixture was not attractive, we went for a beer, but as its temperature was boiling we decided to shorten the night and go to bed. The next day would be inside the complex and we were trying to get ready for that experience in Dadaab.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed